‘Paying’ attention

How much of ourselves do we owe to others?

In 2020, a lot of us were surprised to learn that the old adage “avoiding such-and-such like the plague” held no water. People do not, it turns out, avoid the plague. In fact, they willingly put themselves in its way. They refuse personal protective equipment like masks and avoid vaccinations like … well, something other than the plague. The reasonably anxious and safe among us were aghast. “How could others be so careless?” we asked. “Do they not see the danger ahead? The barrel of a gun we’re staring down?”

We asked all of this from our high horses, unaware that the vast majority of us have been ignoring a plague for decades now. I’m talking about another global pandemic — the commodification, division and exponential shortening of the human attention span in the twenty-first century — an airborne virus in the face of which we all rip off our masks and inhale deeply.

Almost everybody today laments the loss of their ability to focus deeply. It’s not a hollow complaint — writer Johann Hari claims that, statistically, modern teens focus on a single task for an average of 65 seconds before switching, while office workers are able to maintain an average of three minutes of sustained focus. In the face of these metrics, we should all be worried. Human attention is the most valuable natural resource on the planet right now. It’s what every industry is clamoring for, in one way or another.

Take, for example, a typical day for a typical American right now. From the moment Typical American wakes up, TikTok keeps them scrolling with its personalized algorithm. Typical American listens to a podcast at the gym and scrolls Twitter or Instagram between sets, then starts another podcast while in the shower. Typical American goes to the office — metaphorical or literal — and dives headfirst into a disorienting eight-hour-long roller coaster ride of emergent tasks: an email every ten minutes, Zoom meetings on the hour, five projects on the go at once, urgent texts from the kids, phone calls to field and Facebook posts to like during lunch. Typical American goes home, exhausted. The kids watch YouTube on their iPads while they eat, and Typical American watches cable news or maybe a few episodes of something on Netflix. They think about how their bookshelf needs to be dusted. Then they watch a few more TikToks and take a scroll through Reddit. Before going to bed, they lament how tired their mind feels, how fast and distracting the day seems. They desperately wish for their focus back. Then they fall asleep with their phone in hand and the TV on.

Class, what did we notice from this little fable? What information did we glean from the text? What did we learn about this character? From this character? You likely skimmed it. Don’t worry; Typical American would skim it, too. Go back and read it again, slower, and then report back here. I’ll be waiting for you.

First things first: Typical American seems to lead a monotonous, demoralizing life. They long for a return to the “good old days” of reading for pleasure and unbothered, unstructured work time. Yet, while they are participating in this yearning, they are also participating in the distractions. Why? Then, there are the distractions themselves. Some of them are unavoidable; they are other people intruding into our days, requesting help, requesting conversation, requesting work. Try as we might, we can’t control others. But there are other distractions that are wholly in our own courts: the social media apps, the YouTube videos and ceaseless notifications. There’s a sort of addiction going on here, or possibly some sort of Stockholm syndrome. We hate distractions and we can’t stop allowing ourselves to be distracted. The cycle continues until the end of time: we’re distracted because we’re distracted because we’re distracted because we’re distracted.

An important part of our cognition — especially important to mine, being a writer — is allowing our minds to wander. Mind-wandering is the reason why we always have our best thoughts in the shower, on a walk or when we’re trying to sleep. Crucially, mind-wandering is a different process from distraction, though we often think of them as one and the same. It is that unstructured free time where we unburden our minds from distracting, emergent tasks like phone notifications and work projects to instead hop from thought to thought. It is the time when we really chew on the issues nagging at our subconscious minds. It is a vital process for any sort of creative, professional or hobbyist, and more often than not, it is the first thing to go in our world where the work-life balance has turned into the work distraction-voluntary distraction tightrope act.

Mind-wandering was the first thing to go during my own attention crisis, and eventually, the idea of regaining it was the thing that convinced me to once more take control of my focus. Unfortunately, those who feel responsible for their inattention still seem to be in the minority.

Tristan Harris, a technology ethicist, testified before Congress in early 2020 that “we are the free ‘gig workers’ of the attention economy.” Sometimes, I think we neglect to acknowledge that we signed up to be these “gig workers” and have the power to quit this metaphorical job, at least in some respects.

Part of the problem, for sure, is purely neurological. As Harris highlighted in his testimony, “What we call addiction is when technology manipulates and deceives our dopamine reward systems … our physiological workings of habit formation … our reliance on stopping cues … and manipulation of vanity and desire for attention from others.” We cannot help it to a point, the same way that a smoker cannot help but crave nicotine and Scooby-Doo begs for Scooby Snacks. But, to me, that’s not good enough — smokers quit every day and Scooby-Doo wouldn’t have such a problem if the other members of Mystery Incorporated didn’t enable him so much.

There are steps we can and should be taking every day if we’re truly that worried about our shortening attention spans. That means turning off notifications, deleting social media accounts and taking out the headphones, for starters. I get it — it’s hard. I’ve decoupled myself from these attention-sucking habits and I still have switched tabs and wandered away from this article about 30 times. It’s hard to break conditioning. It’s even harder when everyone else around you denies that these habits are part of the problem, when they claim that their daily scrolling is the only thing keeping them sane in such a busy, noisy world. We need to get over our fear of this incredibly hard work and roll up our sleeves, though, if the crisis is even half as severe as we make it out to be.

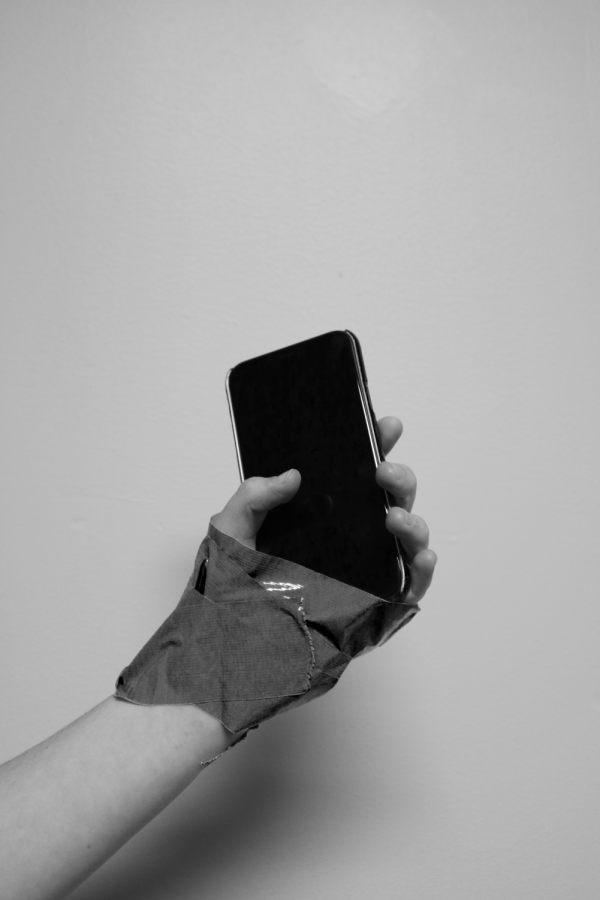

What does regaining our focus mean? It means admitting when we’re addicted and enabled. It means making our smartphones dumber and turning off the email notifications. It means removing ourselves from the incessant hustle that urges our society forward and walking our own slower, gentler path. It means setting boundaries and worrying less about what other people think of the way we live.

Sydney Emerson is a member of the class of 2023. She is from Bradford, Pennsylvania and is an English major with a history minor.

Ethan Woodfill, '22 • Feb 3, 2023 at 9:49 am

This is such a great take, Sydney (as I take out my headphones to read the article)!