Mephistopheles Society: a secret society of the early 1900s

Secret societies of campus past

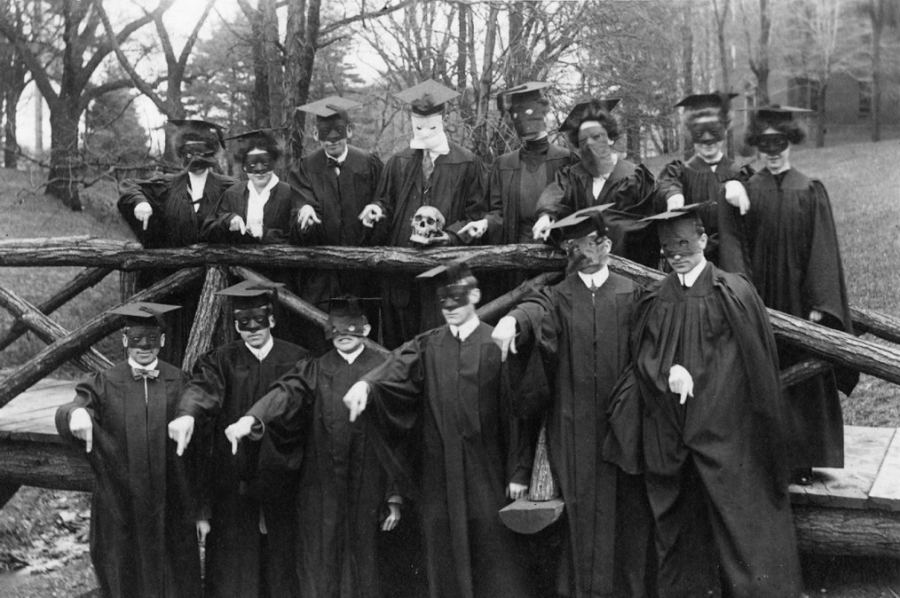

Photo contributed by Merrick Archives. The Mephistopheles society poses on the Rustic Bridge. This photo was published in the 1911 Kaldron, one year before the club seemingly disappeared from campus.

A cloak-and-dagger literary society that congregates over a special symbol on a bridge seems like a story straight out of “Dead Poets Society” — surely not anything that could ever happen on a small, quiet campus like Allegheny College. Yet, around the turn of the century, Allegheny was home to a number of short-lived secret societies.

Perhaps the most flashy of these secret societies was the Mephistopheles Society (sometimes referred to as the Mephistopheles Club) which appeared in The Kaldron for two years straight before vanishing from existence.

On their page in The Kaldron, the club’s page teems with coded words and obscure references — some decipherable, some not. The members, for example, are all listed with the honorary title of “Demon” and are identified by their nicknames. Their surnames are written in a somewhat-inconsistent code of their own invention in which the letters of the alphabet are replaced with numbers and common punctuation symbols. Once decoded, the names reveal a list of illustrious members — including class presidents, salutatorians, editors, and “Patron Demon” Edith Rowley, class of 1905 and longtime Allegheny librarian.

In his 2005 book “Through All The Years: A History of Allegheny College,” Jonathan E. Helmreich, professor emeritus of history, explained that the membership of the Mephistopheles Society intersected greatly with the membership of the Quill Club. The Quill Club was a co-ed student organization first founded in 1899, with membership consisting mainly of those students involved in The Campus, The Kaldron and The Allegheny Literary Monthly.

After making this literary connection, the name of the society comes as no surprise. The society’s namesake is the demon Mephistopheles, who originated in the Faust legend and was popularly depicted in Marlowe’s “Doctor Faustus” (1604) and Goethe’s “Faust” (1808/1832). The demon, who strikes a bargain with disillusioned academic Faust in exchange for Faust’s soul, is a literary invention, having no Biblical basis, according to Encyclopedia Britannica. With the legend’s squarely literary basis and academic bend, the society’s choice in namesake becomes evidently fitting.

It appears that, through shrouding the Mephistopheles Society in mystery — the members’ faces are obscured in the society photo and their names are printed in code — the members of the respectable Quill Club invented a more antagonistic way to appreciate literature on campus.

As for the members’ reasons for founding the society, Helmreich has his own suspicions.

“Though I have no proof, I occasionally wonder if the group were not imitating the Skull and Bones Society at Yale. As members of the Quill Club they corresponded with student leaders at other institutions and no doubt were well aware of the Skull and Bones Society at Yale,” Helmreich wrote in an email to The Campus.

The Skull and Bones Society, a long-standing elite club, has a dark and mysterious aesthetic similar to that of the Mephistopheles Society, who prominently feature a human skull in both of their club photos.

The Mephistopheles Society, however, had far more mundane traditions than Skull and Bones. The only recorded tradition that has survived to present day is the requirement for the members to step on the middle plank of the Rustic Bridge, which had an “X” carved into it, and point downward with their right hand as they crossed over. This innocuous tradition persisted for a while after the society’s apparent dissolution.

After the 1912 Kaldron, mentions of the Mephistopheles Society sharply taper off, with no reason given for the club’s disbandment. Helmreich speculated that, since Skull and Bones was an elitist society and Allegheny did not have a culture of social elitism, the idea of a society based upon Skull and Bones quickly fell out of favor on campus, leading to the abrupt disappearance of the Mephistopheles Society.

Another defunct group at Allegheny closely related to the legendary Skull and Bones Society is Theta Nu Epsilon, a troublemaking secret society that incurred the wrath of usually-genial President William Crawford in the early 20th century.

First founded at Wesleyan University in 1870 with ties to Yale’s Skull and Bones Society, Theta Nu Epsilon was a sophomore social organization that spread across American colleges like wildfire.

In 1945, TIME magazine wrote of the society, “No innocent social fraternity, T. N. E. is an outlaw interfraternity society whose anonymous and generally hard-drinking members often work in secret to control student governments, campus newspapers, fraternity memberships and prom lists, in flagrant defiance of faculty edicts.”

While the Allegheny chapter of Theta Nu Epsilon was prone to mischief, evidence suggests that they were not maliciously attempting to seize control of student life. “Through All The Years” states that Allegheny’s chapter was one of the many unofficial chapters of Theta New Epsilon nationwide, though the Wikipedia page for the organization claims Allegheny’s Omicron chapter as an official chapter of the society.

Some instances of the pranks of Allegheny’s chapter (which neglected to limit membership to sophomores) included, according to “Through All The Years,” cadavers mysteriously appearing where they should not have been, effigies of professors being half-buried on the Bentley lawn, cheese being hidden in radiators, and live chickens being released into Ford Chapel during a service.

Fed up with pranks, Crawford enforced a strict pledge amongst students against joining secret societies on campus. The Crawford administration even went so far as to kick out a student, William Stidger, for wearing a Theta Nu Epsilon pin. Later on, when Stidger requested a letter of honorable dismissal from the college, the college demanded that he surrender his pin in exchange for the letter. Stidger refused.

Turn-of-the-century Allegheny had secret societies to spare — some others include the female societies Skin and Bones and Iota Rho Epsilon, which were based out of Hulings Hall. It seems that students have always had a knack for mischief, whether it be the nineteenth century or the twenty-first. In the words of a 1930 history of Theta Nu Epsilon, “There have always been secret societies and they no doubt will always be in demand.”

Sydney Emerson is a member of the class of 2023. She is from Bradford, Pennsylvania and is an English major with a history minor.