Tarbell’s legacy to be honored with discussion of journalism, reprint of 1904 publication ‘The History of the Standard Oil Company’

It was Saturday, April 14, 1906.

President Theodore Roosevelt delivered a speech in the District of Columbia at the dedication of the House of Representatives offices.

“Under altered external form we war with the same tendencies toward evil that were evident in Washington’s time, and are helped by the same tendencies for good,” Roosevelt’s speech transcript reads. “It is about some of these that I wish to say a word today.”

At the time, Upton Sinclair had already written “The Jungle,” Ida B. Wells-Barnett had published pamphlets and editorials on lynchings in the United States and Ida Tarbell, Allegheny class of 1880, helped shape the future of journalism with “The History of the Standard Oil Company.”

Roosevelt continued his speech by referencing John Bunyan’s allegory “Pilgrim’s Progress,” and addressed the nation, “You may recall the description of the man with the muckrake.”

The muckrake served as a metaphor for those Roosevelt believed focused too much attention on negative news, for those who looked down to shovel filth in perpetuity, for American journalists who had begun to develop investigative methods of storytelling.

Investigative journalists were born out of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, but through Roosevelt’s speech, they were re-born as muckrakers.

Years after Roosevelt’s speech, Tarbell wrote “What I Should Like to Tell June Graduates,” a speech transcript from Oct. 10, 1931, in which Tarbell describes how women graduating from college should treat one’s own imagination.

“Demand honesty from it,” Tarbell wrote in 1931. “Do not let it deceive you. Test all it offers by your good sense — your knowledge of yourself and of your situation. Do this, and depend upon it — you will find both the work and the life which belong to you.”

As Tarbell offered those words to graduates, it had been 51 years since she graduated from Allegheny as the only woman to matriculate in 1876 and one of the first editors on The Campus staff, 37 years since she began writing for McClure’s Magazine and 27 years since she published “The History of the Standard Oil Company,” a collection of articles she originally wrote for McClure’s.

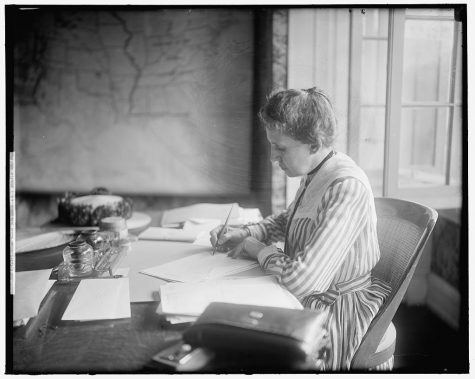

A glass negative of Ida Tarbell, captured in 1905 by the Harris and Ewing Photo Studio as part of a portrait series, is now kept in the Harris and Ewing Collection at the Library of Congress.

This year marks the 161st birthday of Tarbell, an anniversary to be celebrated with cake and coffee at 6 p.m. on Monday, Nov. 5, in the Lawrence Lee Pelletier Library Collaboratory.

The event is open to the community and will involve a panel of speakers and an interactive discussion, sponsored by the Crawford County Historical Society, the Allegheny College Department of Communication Arts and Theatre and the Journalism in the Public Interest Program.

The panelists include Sharon Fraley-Sorg, publisher of the Meadville Tribune, Richard Sayer, photojournalist for the Oil City Derrick and Franklin News-Herald, Marley Parish, ’19, editor-in-chief of The Campus and Matthew Steinberg, ’20, Campus features editor.

Josh Sherretts, president of the Crawford County Historical Society, rounds out the speakers, who will each have 10 minutes to talk about the state of journalism today, said Ishita Sinha Roy, associate professor of communication arts/theatre and Historical Society board member.

“If citizens themselves start to doubt these institutions that are supposed to be the watchdog of democracy, then what happens to our political process?” Sinha Roy asked. “My interest in Ida is less as a person and more as, what did she stand for in terms of the values of journalism?”

A Historical Society board member for about a year, Sinha Roy said she is excited about the energy and sense of purpose the Society has in terms of reviving interest in the county’s history across the community. Sinha Roy cited several pieces of area history about which most people do not, but should, know.

She said Meadville is home to a painting by the brother of Napoleon I at the Baldwin Reynolds House Museum on Terrace Street, was home to John Wilkes Booth as a temporary resident at a former hotel on Chestnut Street as he passed through town and a history of underground railroad connections in the years leading up to the Civil War.

The significance of history, Sinha Roy said, plays an important part in understanding what can be done in the present so history does not repeat itself in the future.

She recalled discussing the Holocaust in one of her classes and the ways in which people “consume” the Holocaust by visiting museums or watching films, yet as detention centers for migrant children have been established in the United States, “we find ourselves unable to act,” Sinha Roy said.

“How do you get people to understand that they are nodding blindly to ideologies that actually destroy them?” Sinha Roy asked. “And how do you get them to feel empowered through history that then encourages them to take collective action, or even individual action?”

One source of empowerment and individual action, according to Sinha Roy, is challenging ourselves and others to become more informed and express informed concern by writing to local newspapers and local leaders.

“When we talk about political action, we’re not talking about just rallies and protests,” Sinha Roy said. “You have to take the time to sit down and think your way through the thicket to make the core idea come across clearly and shine, and in that way, even writing an assignment for a class can become a political act.”

If citizens themselves start to doubt these institutions that are supposed to be the watchdog of democracy, then what happens to our political process? — Ishita Sinha Roy, associate professor of communication arts/theatre, Allegheny College

Tarbell T-shirts, Historical Society holiday calendars and a reprint of Tarbell’s 1904 “History of the Standard Oil Company” will be sold at the Nov. 5 event. Sinha Roy said all proceeds will support the maintenance of historic buildings in the community.

Tarbell’s 1904 collection characterizes the business practices of Standard Oil, the oil producer and refinery that was founded in Ohio in 1870 and disbanded in May 1911 when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that Standard Oil violated the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890.

Under John D. Rockefeller and the company’s other founders, Standard Oil monopolized the oil industry, leading Tarbell on a journey to uncover the company’s history, interests and years of decision-making associated with its founders.

Jane Westenfeld, research and Special Collections librarian for Pelletier Library, said Tarbell was exposed to the oil industry at a young age, growing up in the oilfields of western Pennsylvania and witnessing her father, Franklin Tarbell, struggle to compete as a small-scale oil man.

Tarbell biographers and scholars often regard the “taking on” of Standard Oil as one of Tarbell’s greatest professional achievements and one of the greatest works of investigative reporting.

“Her father told her not to, but she took it on anyway,” Westenfeld said.

The Tarbell reprint is a product of the Cleveland-based Belt Publishing and is part of the Belt Revivals 2018 series, which features works of fiction and nonfiction literature that have been “unjustly forgotten,” said Anne Trubek, publisher of Belt Publishing.

Trubek said the Belt team, which focuses on news and writing related to the American Rust Belt and Midwest, originally wanted to reprint Tarbell’s 1939 autobiography, “All in the Day’s Work.” Due to issues of copyright for the autobiography, Belt decided to include Tarbell’s Standard Oil work in the 2018 series.

“It was one of the most important works of muckraking journalism in the country, it had incredible impact, it brought down (John D.) Rockefeller, it was written by a woman journalist and it’s very much focused on this region,” Trubek said. “So it seemed an obvious choice, especially if a lot of folks didn’t know about it.”

The Belt Revivals 2018 series features three other titles — Sherwood Anderson’s “Poor White,” Hamlin Garland’s “Main-Travelled Roads” and Harold Frederic’s “The Damnation of Theron Ware.” The cover designs for the series are reminiscent of Penguin Paperbacks and Modern Library covers and were developed by Belt’s designer, David Wilson, Trubek said.

Looking to 2019, three revival titles are already available to pre-order on Belt’s website, and Trubek said she would like to reprint titles “as long as we can make the numbers work.”

The reprint of “The History of the Standard Oil Company” became available Oct. 2, and is considered one the most important works on the history of business ever written, according to Paula Treckel, Allegheny professor emerita of history.

“She had to dig really hard and understand spreadsheets and all kinds of information about how Standard Oil and (John D.) Rockefeller and his minions were cheating corners on the market and were driving out the competitors, sometimes legally, sometimes illegally,” Treckel said. “It laid the groundwork for all subsequent kinds of investigations of businesses and how businesses operated.”

Treckel, who retired from Allegheny in 2014, arrived at the college in 1981 and quickly learned the college had a vast collection of Tarbell’s work, notes and correspondence in Pelletier Library. Treckel spent the better part of her second summer at Allegheny working through the Tarbell Collection, which was housed in filing cabinets at the time.

From working through the collection, Treckel said, she gained insight into Tarbell’s journalism, particularly into her pursuit of matters of public interest.

“By laying out the past, you can shape the future when you put up the facts — I mean she believed in facts,” Treckel said. “She didn’t believe that there were alternative facts. There were facts, and she believed that there was a truth. Consequently, when she could lay that out for people, you didn’t have any other choice but to understand what’s right and what’s wrong.”

Tarbell was inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame in 2000 for her professional work, which ranged from exposing Standard Oil corruption to biographing Napoleon I and Abraham Lincoln. Treckel accepted Tarbell’s induction on Tarbell’s behalf and offered remarks at the Seneca Falls, New York ceremony.

“But even though she dined with presidents and potentates, interviewed business leaders and dictators, and traveled around the world, at heart she remained a modest, humble woman, true to the values instilled in her during her youth in western Pennsylvania,” Treckel said at the ceremony on Oct. 7, 2000.

While Tarbell’s contributions to the field of investigative journalism are undoubtedly significant, Treckel said, her lack of support for women’s suffrage and the women’s movement has always been puzzling.

“It really seems impossible to grasp that fundamental contradiction — a woman that perhaps feminists would embrace, women’s rights advocates did embrace, women’s suffragists embraced, as one of them, a role model for them, did not return support for the right for women to vote,” Treckel said.

Though Tarbell’s membership in the New York State Association Opposed to Women’s Suffrage poses ideological questions regarding Tarbell’s views, Treckel spoke with notable enthusiasm about Tarbell’s journalism and the attention she gave to issues so relevant today, including tariff regulations.

Jane Westenfeld, research and Special Collections librarian for the Lawrence Lee Pelletier Library, flips through a diary Ida Tarbell kept in 1905 and 1906 on Oct. 29, 2018. Westenfeld said the Ida Tarbell Collection at the college’s library contains more than 17,000 items.

Shelves of the Ida M. Tarbell Collection materials are housed in the Lawrence Lee Pelletier Library along with Tarbell’s personal book collection.

Like Treckel, Westenfeld spoke with vigor about Tarbell and the more than 17,000 documents housed in the college’s Ida M. Tarbell Collection.

Most documents in the Tarbell Collection were acquired by the college in the late 1940s after Tarbell’s death in 1944. With the help of Paul Giddens, Allegheny history professor who died in 1984, and Sarah Tarbell, Ida Tarbell’s younger sister, materials made their way to Allegheny.

The Collection, however, was obtained in part, and Allegheny does not have Tarbell’s papers or correspondence regarding Standard Oil. Those documents, Westenfeld said, are located at the Drake Well Museum in Titusville.

“It’s not good for a collection to be split, first because it’s harder to staff, and second, it’s not good for the continuity of the collection,” Westenfeld said. And when people contact her about Tarbell’s Standard Oil material, she tells them, “We don’t have it.”

But even without Standard Oil documents, the Tarbell Collection at Allegheny is remarkable, according to Westenfeld. The collection is comprised of four series: Correspondence, Research Writings and Topics, Autobiography Material and the Lincoln Collection, as well as Tarbell’s own collection of books. However, books from her time as an Allegheny student are not part of the collection, Westenfeld clarified.

Most people who contact Allegheny about Tarbell, Westenfeld said, are interested in the Lincoln Collection.

One item Westenfeld finds particularly interesting is a pair of letters regarding Tarbell’s research and books on Lincoln.

In a letter dated Dec. 1, 1937, Parke E. Doland wrote to Tarbell expressing his gratitude for her Lincoln writings. Doland explained that he was raised in Virginia to know and love Robert E. Lee, J.E.B. Stewart and Stonewall Jackson and heard his grandmother say, “They didn’t kill him soon enough,” when she learned of Lincoln’s assassination.

“With this background, you can know that I considered Lincoln a great black blot on American history,” Doland wrote.

After informing Tarbell that he read her Lincoln books, Doland wrote, “For the very first time, I was able to see the man with unprejudiced eyes.”

Nearly three weeks later, on Dec. 20, 1937, Tarbell responded to Doland, thanking him for his letter. She wrote, “What we all need in working our way through this world is a better understanding of the man on the other side of the question.”

Westenfeld wondered what Rockefeller would think of that.

Since 2000, Westenfeld has been working with the Tarbell documents when the library began to microfilm them, a process in which small photographs of the documents are stored on rolls of film.

By 2008, the library began a digitization project that lasted between seven and eight years, Westenfeld said.

During the digitization process, an Indiana-based journalist would email Westenfeld at least once a month asking, “When is Lincoln going to be done?”

With a laugh, Westenfeld said she would respond, “It’s going to take a while.”

Westenfeld expressed similar frustrations to those of Treckel, as she recognized Tarbell’s strength as a pioneer for investigative reporting along with her opposition to women’s suffrage.

“If she could have been that strong in the women’s movement, she would have had a lot to contribute,” Westenfeld said. “What about the rest of the story, Ida? What was it like working in the publishing world dominated by men?”

With women in general and her own personal life, Westenfeld said Tarbell “held back” and only offers glimpses of herself outside her professional circles in her collected documents.

Those glimpses, according to Westenfeld, include Tarbell’s continued commitment to Allegheny after she graduated, strong ties to her family members, who she cared for with dedication, and a move to a farm in Connecticut in 1906 so she could be reminded of her upbringing.

Tarbell’s handwriting also became progressively illegible as she developed Parkinson’s disease, which has made digitizing some materials difficult, Westenfeld said.

Tarbell switched from handwriting to using her fingers on a typewriter as the disease progressed. Eventually, she held two pencils, one in each hand, to tap typewriter keys, Westenfeld explained as she gently motioned the typing.

While glimpses may not tell Tarbell’s full story, they contribute to what Westenfeld described as “a fascinating life.” Tarbell kept scrapbooks where she would cut out clips about Mary Todd Lincoln as part of her Lincoln research, and she would use hat pins to pin clips and scraps of paper to letters.

Tarbell’s legacy is alive in her years of muckraking work, in the many questions her life causes us to ask, in the generations of journalists who have since served as watchdogs and in the extensive collection of her materials — about which, history is written.

“One thing I would like to someday hear is her voice,” Westenfeld said softly. “After reading all of her words, what does her voice sound like?”

Ellis Giacomelli is a senior majoring in environmental science and minoring in journalism in the public interest. She serves The Campus as a features editor...