Late in the summer of 2002, professor of biology Milt Ostrofsky was patiently wading his way through the warm waters of Sandy Lake. Just twenty thousand years ago, he would have been walking on ice.

In the last Ice Age, an enormous glacial sheet that began in the Arctic reached out with icy arms to hug Pennsylvania from above, slanting down to cut off the boxy state’s top corners. Occasionally, the retreating glacier released a piece from its edges. Those fallen masses of ice carved out kettles in the earth where they landed, and the kettles became modest lakes. Sandy Lake is one such spot—a little over a mile long and half a mile wide in the northwestern part of the state.

Prior to that summer, Ostrofsky had discovered a thriving zebra mussel population in Sandy Lake’s waters. A single zebra mussel takes up no more space than your fingernail, but in large numbers the creatures can clog pipes, coat boat hulls and docks and cut the soles of beachgoers’ feet with their sharp shells. Their invasive presence has already driven out native mussel populations by monopolizing the lake’s hard surfaces—stones, other mussels, even the rigid stems of lily pads.

Ostrofsky wanted to publish his encounter with the mussels, and he only needed some background on their habitat.

“We wanted to put together a story of the lake,” said Ostrofsky.

But what began as a contextual footnote to zebra mussel population expansion quickly transformed into a fascinating narrative of the lake itself.

“No One Alive Knows About This”

One morning, a tattered copy of Pennsylvania’s 1897 fishing commission report arrived from New Hampshire (Pennsylvania, oddly enough, did not have a copy of its own). In it, Ostrofsky found something surprising: sometime in the mid-1800’s, acid mine runoff had devastated Sandy Lake so that every catfish, sunfish, perch and pickerel had been killed in the pollution’s wake.

To someone standing on the lake’s quiet wetland shoreline today, the report’s revelation is a startling one.

“If you look at Sandy Lake now, it’s an absolutely beautiful lake,” said Ostrofsky.

In fact, it’s one of the clearest lakes that Ostrofsky says he’s ever worked with.

The obscure report’s summary left Ostrofsky with what he called “a tantalizing little piece of information” and a few unanswered questions. For instance, the report briefly alluded to ongoing protests against the pollution and “early legislation…which would completely put a stop to the evil.”

How did the lake manage to recover from a complete extermination of life, Ostrofsky wondered, and how long did it take?

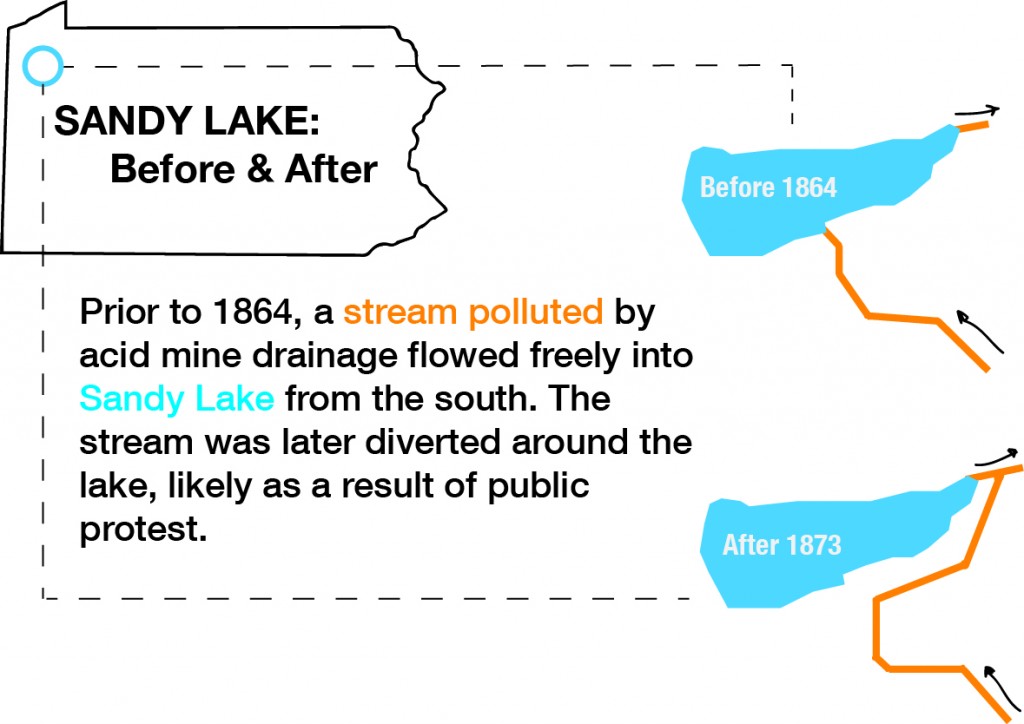

The only answers he could find lay in a pair of old county maps—one from 1864 and another from 1873. The earlier map shows a brook connecting the nearby Mercer Iron and Coal Company to Sandy’s Lake’s southern coastline. By 1873, that thin strip of water traces along the edges of the lake, avoiding it completely. But both documents lack explicit evidence detailing the lake’s quick route to pollution and recovery.

Ostrofsky likened his situation to old Columbo reruns on television, where the traditional detective story is inverted and the murderer’s identity is revealed in the opening scene. The greater mystery, then, stems not from lack of culprit but from lack of context.

“You see the crime; you know what the crime is,” Ostrofsky said. “But you have no idea how it happened and who was involved.”

Sometime in the last two hundred years, pollutant runoff brought all life within Sandy Lake to a temporary halt. The perpetrator was undoubtedly the long-defunct Mercer Iron and Coal Company with its careless waste disposal. By luck, Ostrofsky had become the first person in centuries to stumble upon evidence that any of it—the lake’s surprising brush with death, its apparently rapid resurrection—had happened. He wanted to be the first, too, to fill in the context.

Today, Ostrofsky recalls his discovery with excitement, especially his first thought after closing the report:

“No one alive knows about this,” he said.

In a flurry of old documents, the direction of his research had changed. Before he knew what was happening, Ostrofsky had set out to piece together the recent history of Sandy Lake.

Deconstructing the Past

The secrets to Sandy Lake’s mysterious past lay in the soft, cake-like layers of sediment deposited at its base. Minerals and the tiny, dead bodies of phytoplankton have piled up over time there and scientists like Ostrofsky can cut away at the accumulated layers to learn how a lake’s environment has changed over time. These scientists who take a closer look at lakes’ histories are formally called paleolimnologists, a title that translates literally to “those who study old lakes.”

For his research, Ostrofsky drives weighted, narrow tubes into the lake’s floor to collect two-foot long sediment cores, a process he likens to placing your thumb over the tip of a straw to suction up a milkshake. He then pushes the column up through the bottom of the tube and slices small sections off the top. Each section contains information about a brief period of the lake’s past.

Ostrofsky was hoping to find evidence, first, of the massive runoff contamination described in the 1897 fishing report.

When mine drainage first enters a body of water, it introduces iron and sulfur to the environment. The iron oxidizes to rust, which is why in some places you can find streams that flow a sickly, bright orange. The mine’s sulfur waste oxidizes to sulfuric acid, and that acid is the main culprit responsible for unbalancing delicate water chemistry and killing native fish populations.

When Ostrofsky examined his sediment cores from Sandy Lake, he found an abrupt spike in sulfur levels that corresponded to the mine’s development around 1865. Levels fell again in the parts of the sample core that corresponded roughly to the time period in which the brook carrying mine waste was being diverted around the lake.

From there, Ostrofsky continued to piece together the lake’s recovery through diatom fossils in the soil layers. Diatoms are unicellular creatures that look a bit like tiny glass beads. They are classified according to their tough, silica shells, which can often be wonderfully triangular, spiked, or star-shaped. Extracting and identifying these silica skeletons allows us to glean information about past climates.

To understand how diatoms might help scientists piece together geological histories, Ostrofsky offered the example of a cactus. A person would expect to find a cactus only in dry, desert climate.

“You can do the same with diatoms,” Ostrofsky said. “We can reconstruct what the environment must have been like based on which species were dominant.”

Models can suggest the likely pH of a lake based on the dominant diatom species at the time. In Ostrofsky’s case, the models of Sandy Lake signaled a tenfold acidity increase in the short period of acid mine pollution.

The Road to Recovery

Recovering from a terrible bout of pollution is a straightforward process for a freshwater body like Sandy Lake once someone eliminates the source of pollution. This is largely because most lakes connect to other bodies of water. Water is flushed out slowly, and a small lake’s contents can be replaced gradually over the course of a year or so.

Thus, after the polluting brook was diverted away from Sandy Lake the tiny lake naturally renewed its stock of water by feeding into larger rivers.

Though Sandy Lake lies close to three major population centers—Pittsburgh, Cleveland, and Erie—it has maintained its high water quality for many years. The lake’s private ownership keeps visitors to a minimum, and those cottagers who do lease property along the shore face strict rules against septic systems that would allow runoff to enter the lake.

And though the coal mine’s pollution was disastrous in the short-term, the brook diversion that resulted from the conflict effectively halved the amount of surface water draining into the lake from nearby areas. This is important because surface water accumulates artificial fertilizers as it moves across developed land. When nutrient-rich water reaches a lake, it can spark quick, out-of-control bursts of plant growth.

Paleolimnological studies, like the one at Sandy Lake, primarily consider what a lake looked like long ago. Still, they do so with a mind towards healthy lakes now and far into the future.

“It’s a pretty useful tool to reconstruct the history of any lake,” Ostrofsky said, “particularly when there’s an interest in lake remediation and improving water quality. It gives you a tool to set reasonable and attainable targets for lake restoration.”

Ostrofsky guesses that there are only about 300 other paleolimnologists active in the field. They make up a tiny and often overlooked community within ecology—but one that appreciates the value of what lies beneath a body of water.

Since Sandy Lake, Ostrofsky has moved on to a more challenging subject: Lake Champlain, which lies along the Canadian-American border. Unlike the much smaller Lake Sandy, Champlain is big enough to require at least 13 cores from different regions of sediment.

Ostrofsky spent the last year away from his classroom on sabbatical, where he finished up the analysis of those cores in his lab.

Still, he wonders if he will ever have enough time to do all that he wants to do.

“Time is short,” he said. “And I could do this forever.”

John collenette • Sep 18, 2021 at 8:08 am

What can I say, greatest time. Of my life. I worked for Homer off and on for over 20 years. I lived at the lake for 4 years. Worked hard, played hard. I got to know a lot of great people like a lot that have committed already. I grew up on Forest st and played in the woods behind my house so what I can add to this story is that I know for a fact that just off of Mine street on the north side just a bit off the road there are a couple sulfur pits that are still pumping out sulfur. I fell into one when I was younger and my clothes had to be thrown away, Prue orange and it would not wash out. The creek tcoming off the hill behind my old house runs underground through stoneboro . This creek joins up at Gilligan’s gas station and then runs down into the swamp of the lake. I have hunted every hillside east, West, north and south and know of no other sulfur creeks other than the one behind my old home off of mine street. I know for a fact that many people, a lot of my dear friends have died of cancer and other terrible illnesses in the town of stoneboro. Way too many. My heart will always belong to this lake and area.

Rodney HERRON • Sep 17, 2021 at 12:33 am

Born in 1947. As a kid would walk the tracks from Sandy Lake to Stoneboro Lake. I can still see Mrs Greer in her straw hat. I would pay her and she always had a kind smile.Then she would stamp you hand. I’d hurry into the bath house, get a basket and change. I loved the twin diving boards and the real high diving board. Boy we had a lot of fun there and so many great memories. Oh, fishing at night in a boat catching largemouth bass was a thrill. It was just so nice out there on a moonlight night! I would love to rent a cottage there. Since I have the owners name I’m going to check it out. Thank you for this article. My Nickmame is Nub

Gabe Kish Sr • Aug 11, 2021 at 12:34 pm

This is fantastic. I very much appreciate that folks have so much history to give about the area. My wife and I are new property owners in the area. We bought a place just north of town. Our water has a very high iron content, as I’m sure most places with wells deep enough around here, do too. Anybody else?

Gary Gyder • May 25, 2020 at 9:46 pm

Homer Widel was my uncle

And we called

Helen , aunt Helen growing up No better place to spend summers!

Edward Bromley • Mar 27, 2020 at 9:23 am

To this day I can remember waiting at the lake for Helen Greer to show up in her old Mercury. We used to ride our bikes to get there. Fond memories of summers there.

Albert Jesionowski • Aug 14, 2019 at 2:06 pm

I’m not sure about all of the rerouting of the creek up at Sandy Lake, but my Aunt used to rent Cottage 15, Blanche/Ed Michalski. Unfortunately, both have passed, and then around 1978, my family started renting Cottage #9. I have been going up there since I was 5, my father since he was 5, unfortunately, he passed away this past January. They rented that place for 42 years. The Jesionowski/Michalski’s have had great memories at that place. I loved it up there, and my kids have been going up since they were born. My oldest is now 17 and my youngest is 14. Unfortunately, after my father’s passing in January, we just couldn’t pay for the rent any longer. My father was a lifeguard at the beach, along with several of my cousins, sister, and myself. We all enjoyed the quiet setting the cottage had to offer. My mother used to tell me stories of going down to Cottage #5, where Hellen used to have her cottage and sit on the porch talking to her about the early days of the lake. It’s a shame that the time goes so fast, and the History just fades away. I hope someone is able to bring the History back to that lake, as well as the town that has supported it all of these years.

Gretchen Freni Augustyn • Jul 10, 2019 at 5:21 pm

My grandparents came to Sandy lake in about 1921 and had a summer cottage . They would walk each day, along the railroad

tracks from Sandy Lake to the lake in Stoneboro. People have been enjoying the lake,, swimming an boating since the turn of

that century. It is so sad to think that the public beach is no more, just like McKeever Center (mentioned above) My father was

one of the founders of McKeever. My heart breaks, knowing both of these amazing places are no longer operative. My sister and

I still own the farm in Sandy Lake where we grew up. Although I left Sandy Lake in the fall of 1957, my heart remains there.

Cindy Blinco • Apr 14, 2019 at 11:44 am

A group of us have been trying to find some facts about not only the coal mining factory and the asbestos factory. In my research their have been numerable people from our area that have had cancer and sadly some have passed. I do not know an exact number but if anyone can help me with this and or the correlation between this and the asbestos and other dumping seem to be directly connected. Just has to be more than coincidence.

Mary Sherwin • May 28, 2018 at 9:21 pm

I can’t imagine my childhood (1953-1973) without images of friends and family have fun at Sandy Lake. I also remember riding our bikes up and down the huge piles of asbestos in the warehouse. Yikes.

Jason A. Sippola • May 9, 2016 at 10:26 pm

The Cleveland, Painesville, and Ashtabula Railroad completed the rail line to Stoneboro, PA in May of 1864. The line ended at Mercer Iron and Coal Mine No. 1. The railroad extended the line to Franklin, PA between 1865 and 1867. During this extension the offending creek was relocated by the railroad. This rail line came under control of the New York Central Railroad. I posses New York Central Railroad valuation maps that show the original and relocated creek; it is labelled as ‘Sulfur Creek’ on the map. So, the railroad responsible for creating the borough of Stoneboro also saved the ecosystem of Sandy Lake.

Jim Tibor • Feb 7, 2018 at 10:35 am

Not having seen the map you refer to I of course don’t know what it indicates for the course of the stream after it was relocated. However, I can tell you with certainty that up until about 1960 or so, the stream continued to flow into Sandy Lake, but entered the lake further to the eastern end of the lake near its outlet. About that time the stream was relocated again from where it crossed under the RR tracks directly into the outlet itself. During that period I can tell you that the stream carried raw sewage from some of the homes in Stoneboro located along the stream.

Jow Hueks • Oct 31, 2015 at 3:13 am

Great article. My folks owned Sandy Lake and my sister runs it now. It was a wonderful place to grow up. Homer Widel, my stepfather, took great pains to make sure that no pollution fouled that precious water.

Roman Amon • Mar 8, 2018 at 5:17 pm

My friend above’s name is Joe Huels there is a spell check issue with his name.

I was born in 1953 & lived on the hill connected to the north side of Sandy Lake the Lake often referred to as Stoneboro Lake to the natives here. I have enjoyed this area for 55 of my 65 years here. Rocky Basin now known as the former McKeever Environmental Center is many acres of woods & a Creek called Mucheoun Run

The area is full of shallow underground coal mines & much of the water runoffs flush iron up from it’s natural environment.

There was once an Asbestos Factory on the property just East of the Sandy Lake that has since been torn down consisting of several multi story concrete buildings, where Asbestos was processed & consequently ran off right through the lake for years.

Environmental protection was evidently not a concern in those days.

The Above article is an interesting document of some of the History here.

Homer was a great guy, Helen Greer managed the lake before Homer now Julie Widel/Marsteller manages & owns it now.