Single Voice returns with Ferrence and Barnhart, ’07

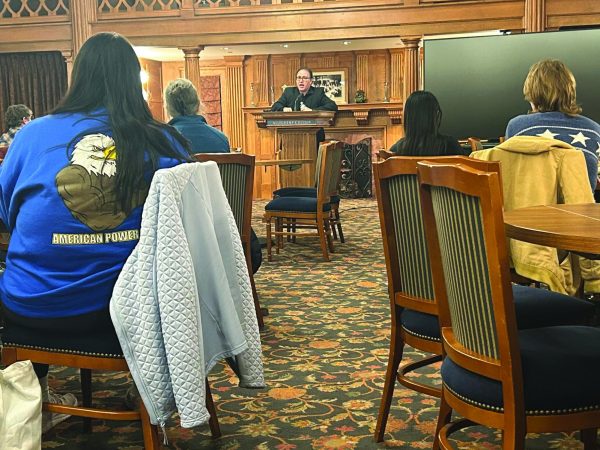

Irish author James Joyce once wrote, “Writing in English is the most ingenious torture ever devised for sins committed in previous lives.” Previous lives were the specter that haunted the Single Voice Reading on the evening of April 14 in the Tillotson Room in the Tippie Alumni Center at Cochran Hall.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, writers were invited to Allegheny from across the globe to participate in the decades-long series, visiting classrooms and interacting with Allegheny students outside of the requisite formal reading. Now, after a two-year hiatus, the series has been re-launched with English faculty in the spotlight. In the fall, Assistant Professor of English Mari Christmas and Professor of English M. Soledad Caballero read from their fiction and poetry, respectively. This spring, it was Department Chair and Associate Professor of English Matthew Ferrence and Visiting Professor of English Graham Barnhart, ’07, who showcased their work.

An Allegheny alum who completed a senior comprehensive project in poetry, Barnhart participated in the December 2019 Single Voice Reading — one of the final readings before the pandemic. It was there that he read from his then-new book, “The War Makes Everyone Lonely.”

Now, three years later, Barnhart returned to the Tillotson Room with a changed perspective.

“To tell you the truth, I’m not terribly excited about those poems anymore,” Barnhart said to the audience. “They feel like somebody else wrote them.”

Ferrence expressed a similar sentiment in his reading, indicating that his forthcoming memoir, though meaningful, was not the writing that best represented himself that evening. The book, “This Is How We Lose: The Poetics of Rural Political Abandonment,” is a political memoir about his unsuccessful bid for the Pennsylvania House of Representatives in 2020, a past life which Ferrence is still trying to make sense of.

“That’s enough of the memoir,” Ferrence said, after reading only a few paragraphs. “I’m going to read fiction.”

The traditional structure of a reading is simple: a writer takes the podium and they read a short story, some pages of an essay or a series of poems. At this reading, however, both writers decided to subvert this structure, instead sharing multiple drafts and preliminary notes for unfinished projects with the audience.

“Writers, we like to talk about ‘process’ in workshops, and it’s interesting to us there, but when we read somebody’s work, we tend to encounter it as this polished, finely finished thing,” Barnhart said. “You don’t really get to see all the work and time that went into it.”

Ferrence, in his allotted time, shared three excerpts of what he intends to eventually turn into a novel, each focusing on a different character: Mooney, Lauren and Row.

The characters live in a nation that, through the power of total electrification, experiences 24-hour daylight. Mooney and Lauren are natives of an Appalachian darkness refuge, home of the only natural darkness left in the country. Row is a part of the infrastructure that threatens to take this sanctuary away. As Ferrence made his way through the three passages, he stopped to comment on unfinished sections and half-developed plot ideas, recognizing the time that it takes to develop a piece of fiction.

Barnhart took this principle even further by presenting a slideshow of different drafts of a still-in-progress poem.

“I liked (the reading) a lot,” Christina Kljunich, ’23, said. “It was kind of that chaotic … nature that everyone knows and has gone through as a writer. So it made it a little bit more personal, I think, than other readings I’ve been to.”

The poem that Barnhart presented was an erasure, a style in which the poet takes an already-existing text and blocks out words. The words that remain constitute the poem. In his case, the text he has been erasing is personal. It is a peer-reviewed article that he wrote about his experience treating an Afghan soldier’s gunshot wound for 13 hours after falling under enemy fire on a deployment in 2016.

He began with his first draft, in which he followed strict, self-imposed rules: all words must be kept in their original order and no words may be partially erased to spell out other words. He also made the aesthetic decision to keep the original text visible. The result was a draft with which Barnhart was dissatisfied. In hindsight, though, it was necessary.

“I needed to write this draft,” Barnhart said. “At the time, I didn’t like anything I was writing … I was becoming really discouraged and had only just begun to come around to the realization that maybe the way I was feeling about writing was also related to my symptoms of depression and post-traumatic stress … I seemed to have lost the ability to access my voice — my authentic voice — in writing.”

Voice is everything when you are a writer. It informs the subject matter that you tackle, the people and places that grip your imagination and the themes that you revisit again and again. This is something that Ferrence has also been focused on lately.

“(Writing) is all about shifting perspectives,” Ferrence said. “As human beings, we’re often trapped in certain moments that we’ve experienced, and there’s some element of us that’s always there … I think all writers are always stuck and will never escape those foundational moments, and so we get to come to it from different places. We were built there, but we’re not trapped. Our artistic urge is about rebuilding our pathways through it.”

Over the course of the evening, the audience watched as Barnhart’s first draft morphed into a much different second draft, built upon the one phrase from his initial attempt that he liked: “the field extended in the field,” and eventually a third draft, inspired by the ancient pastoral tradition, in which he gave himself permission to spell out the word “sing” using letters poached from other words in the article.

Barnhart explained that he began to think of his experience in the field as that of a shepherd — himself, the other medics and the casualties — singing a song. This is the direction in which he sees the still-unfinished poem heading. It is also more than a poem, Barnhart explained. It is a reckoning with himself.

“As I have been slowly … working on developing a better understanding of my mental health, this project has transformed from a weird little experiment to a very concrete representation of my relationship to language and the weight of traumatic experience,” Barnhart said. “There’s still a long way to go … but (the poem) feels like something to me, and that feels like massive, massive progress.”

Sydney Emerson is a member of the class of 2023. She is from Bradford, Pennsylvania and is an English major with a history minor.