Allegheny’s murderous professor

The Penny Dreadfuls

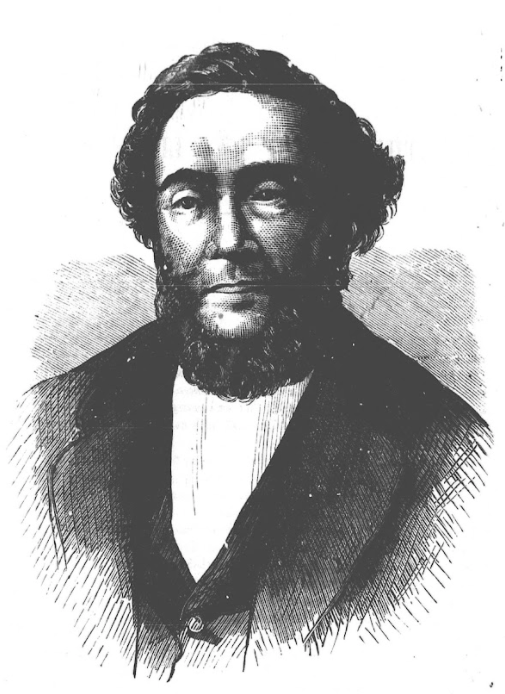

Photo source: Wikipedia Edward Rulloff, also known as James Nelson, is pictured here. Ruloff taught at Allegheny briefly under a psuedonym. Ruloff killed his wife and young daughters in 1844, prior to teaching at Allegheny.

In 1858, an English philologist named James Nelson arrived in Meadville with the hopes of earning a professorship at Allegheny College. He was a skilled teacher who knew Latin, Greek, German, French and Italian, and was in the midst of developing what, in his opinion, would be a groundbreaking linguistic theory.

He was also, in reality, a serial murderer who had spent 12 years incarcerated before his recent escape from jail — a man better known as Edward Rulloff.

In 1844, Rulloff killed his wife and young daughter before reportedly dumping their bodies in Cayuga Lake, N.Y. Unable to convict him for the murders without a body, the jury instead found him guilty of kidnapping. He was sentenced to 10 years in prison and was subsequently found guilty of murdering his daughter in 1858, but escaped from jail after this conviction.

Rulloff was not an ordinary criminal. In prison, he taught himself philology and tutored students from his cell. As The New York Times described him in 1871, Rulloff was “a student by instinct and … a scoundrel from choice.” Indeed, Rulloff was a gifted academic, with a natural curiosity and a wide range of intellectual pursuits.

Journalist and author Kate Winkler Dawson spent the first season of her podcast, “Tenfold More Wicked” covering Rulloff’s exploits and has recently completed a book on Rulloff.

“People with psychopathy have, usually, a singular focus,” Dawson said. “That shows you how motivated he was … (becoming a professor) was his dream.”

It was this narrow focus on being a member of the academic community that brought Rulloff to Allegheny immediately following his escape from jail, with the plan of reinventing himself as Oxford man James Nelson.

Rulloff, as Nelson, approached President John Barker and requested to be tested in languages, a practice that, according to Dawson, was commonplace in the 19th century. After having passed the test with flying colors — and seemingly fooled English-born Barker with his fake accent — Rulloff was presented with a certificate denoting his proficiency in multiple languages.

Most sources — including “Tenfold More Wicked” — suggest that Rulloff then proceeded to teach at Allegheny for a brief period in a temporary position. There are few other records which suggest that he may have taught at Washington and Jefferson College, or possibly both schools. In Rulloff’s own words, he “made (himself) useful,” leaving the extent of his duties at the college ambiguous.

Regardless of where he worked, his effect on others was clear. Rulloff was a charming colleague and impressive teacher who never let on to his deadly nature. This ability to put up a good front is a hallmark ability of psychopaths: “Rulloff would say anything to anyone. He didn’t value anybody but himself because he thought he had a higher purpose,” Dawson said.

When the semester came to an end, it was clear that despite his merits, there was not a permanent position for Rulloff at the college. Instead, he was recommended for a job at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Faculty pitched in for Rulloff’s expenses, and he was just about to leave town when he received an urgent letter.

Albert Jarvis, the son of the Ithica, N.Y. undersheriff, had helped Rulloff in his escape. He had since been rejected by his father and now demanded repayment from Rulloff. Rulloff, in turn, robbed a jewelry store for funds to support Jarvis and was promptly arrested. A lack of self-preservation and forward thought, according to Dawson, is another hallmark sign of psychopathy.

After Rulloff’s arrest for robbery in Meadville, his teaching career was as good as over. He would never grace a classroom again, instead moving to New York City and adopting the lifestyle of a crazed academic as he pored over his manuscript night and day, supporting his dedication to philology with criminal activity. It was a botched robbery attempt in 1870 in which one victim was murdered and both of Rulloff’s partners drowned that sealed Rulloff’s fate.

Rulloff’s trial began in 1871 and immediately attracted the attention of the public. Mark Twain notably came to Rulloff’s defense, writing in a letter to the New York Tribune in 1871: “Here is a man who has never entered the doors of a college or university, & yet, by the sheer might of his innate gifts has made himself such a colossus in abstruse learning that the ablest of our scholars are but pigmies in his presence.”

Twain, a vocal opponent of the death penalty, was part of a larger culture in the late nineteenth century in which intellect was valued as a rare commodity — one perhaps more important than punishment for capital crimes.

“In the 1800s, people in academia were really highly valued even though they were kind of rare,” Dawson said. “(Hanging Ruloff) literally seemed like a waste. If you were going to hang him, it was going to be a waste of somebody who could actually contribute to society.”

Despite protests by the public, Rulloff was hanged on May 18, 1871. In a macabre coda, his unusually large brain was taken from the body and preserved in a jar at Cornell University, where it remains to this day.

As for Rulloff’s connection to Allegheny, Dawson believes that the school may have had more of an impact on him than previously thought.

“Being at (Allegheny) is the closest he ever came to being what he wanted to be, to achieving the goals that he had,” Dawson said. “So I think he regretted for the rest of his life that he left Meadville. That was the gates of heaven for him.”

Sydney Emerson is a member of the class of 2023. She is from Bradford, Pennsylvania and is an English major with a history minor.