Berry film poetically documents industrialization of agriculture

The Foundation for Sustainable Forests, in partnership with the French Creek Valley Conservancy and Allegheny College, hosted its first installment of this year’s “Our Woods & Waters Film Series” at 7 p.m. on Friday, Feb. 23 in the Quigley Auditorium.

The title, “Look and See: A Portrait of Wendell Berry” suggests the film is about one man, but in reality, it is about the movement he spent his life building.

The screening was attended by Meadville community members with several Allegheny faculty and students. A discussion period followed the film.

The film begins with the voice of Wendell Berry reading aloud his poem, “The Objective.” Artfully overlain by footage of life across the globe, the combination is very moving, and the message of the poem is not lost as images of a simple, quiet walk through the woods replace the noisy global bustle.

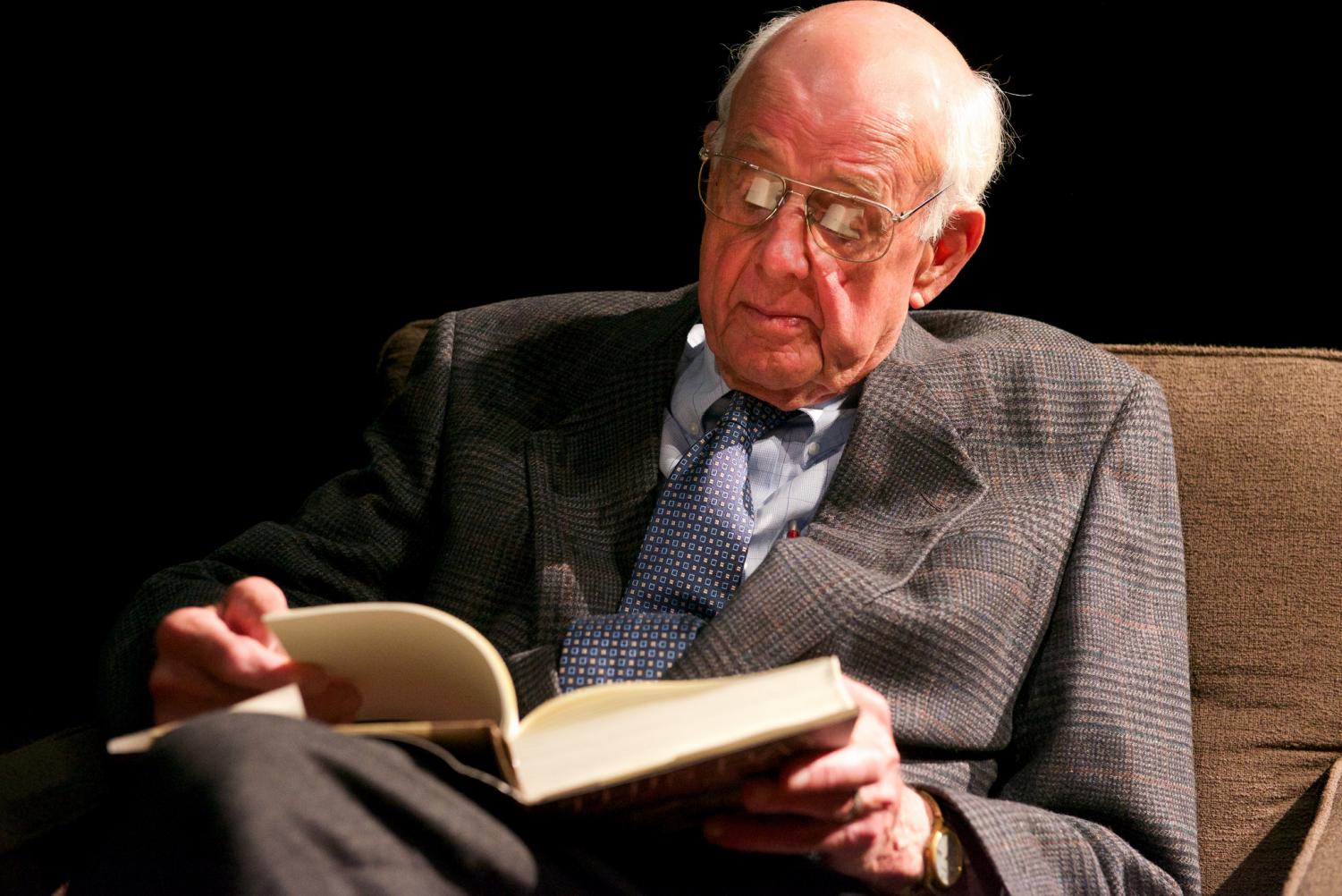

Wendell Berry reads poetry at the 2014 Festival of Faiths in Louisville, Kentucky. The theme of the 2014 festival was “Sacred Earth Sacred Self.”

I encourage anyone reading this to read “The Objective,” as it has quickly become one of my favorites. Berry also opens by dedicating the film to the memory of his longtime friend, James Baker Hall, whose beautiful photography is featured throughout.

The film is divided into six chapters and a brief epilogue.

Chapter One is titled “Imagination in Place” and features Berry’s daughter Mary Dee discussing her childhood relationship with her father, who on walks throughout their farm and forest would tell her to constantly “look and see” — and remember what is good, bad, beautiful and ugly.

Scenes of farmers harvesting tobacco by hand parallel old photographs of Berry’s family and friends doing the same, and farmers discuss why they love farming — the beautiful necessity that brings people together, a raw idealism and the reality of accepting less than ideal practices.

Chapter Two, “The Unsettling of America,” dives into the issue that inspired Berry’s career as an activist and essayist focused on agriculture.

Farmer Steve Smith describes the industrialization of agriculture as the relinquishing of the artistic elements of farming. The industrialization that has increased our food production so incredibly has also caused the consolidation of American farms — fewer but much larger farms.

Remaining small farmers are in a constant race to just stay on top of the debts required to stay in business.

Berry insists today’s farming industry is based on a false ideal for a false economy which works against nature and enslaves many people — and not just American farmers, but immigrant farmers as well, who out of economic necessity travel annually from Mexico to Kentucky, North Carolina, Tennessee and Virginia where there is not enough local farming labor.

Through policy, we have wiped American farmers out. This chapter is one of the more dense ones, but it sets the stage for the remainder of the film.

Chapter Three, “Nowhere,” shows us empty towns where farming communities used to thrive, and Mary Dee talks about negative attitudes towards poor rural communities — that if their people were smarter, they would do something else besides farm.

Berry discusses what it means to be part of a “nowhere” place — an honest place mistaken for “nowhere” suffers in that it is designated as a sacrifice, and it faces soil erosion, toxic air, poisoned water and destroyed community.

As someone who grew up surrounded by rural communities, this and the previous chapter hurt my heart deeply. But Chapter Four, “It All Turns on Affection,” lightens up with touching insights by Berry’s wife Tanya about making somewhere a home by just being there.

Wendell, meanwhile, shares his thoughts on fixing broken things — you don’t have to put everything back together, just put two things back together.

Chapter Five, “A Home Coming,” begins to address deeper resolutions for agricultural industrialization.

Berry describes the main purposes of industrialization — to replace people with machinery and to concentrate wealth into fewer and fewer hands.

Berry and Tanya both point to a different kind of life, in which people love doing their work out of pure enjoyment and live an honest life on a farm. This gentle chapter bridges into Six, “The Handing Down,” in which Mary Dee outlines the solution for which Berry has been advocating for many years.

Mary Dee explains the importance of local food movements and their role in inspiring cultural changes. She argues movements cannot stop at farmers’ markets and must also address land use and the economies of food producing places.

Berry affirms the need for a healthy farm culture “based on familiarity, on people soundly established upon the land,” a culture that “nourishes and protects that human intelligence of the land which no amount of technology can replace.”

Berry finishes by saying that if we do not ensure this happens for subsequent generations, we not only invite calamity, but we also deserve it.

The Epilogue, called “A Vision,” features Berry reading a poem of the same title, which describes his hopeful view of the future.

“The abundance of this place, the songs of its people and its birds, will be health and wisdom and indwelling light,” Berry said. “This is no paradisal dream. Its hardship is its possibilities.”

After asking some of my peers for their thoughts on the film, the most common responses were the pacing was tough to follow and the film was surprisingly barren in material about Berry’s own life.

In fact, the film never showed current footage or photographs of Berry — only historical photographs from media outlets or older pictures taken by Hall. This may be explained by a remark made by Berry in the film itself — he does not get involved in film, as he prefers writing, because of how limiting a film lens can be.

This may have also been an artistic choice on the part of the directors, since the film was definitely framed more around the movement to return to artistic agriculture rather than the man behind it.

Berry’s way of speaking is deep and soothing, and his poems flow, so it is easy to feel tired and even bored after a while. However, the slow pacing of the film parallels the gentle, idyllic farming life to which Berry hopes the agricultural industry will return. I cannot help but mirror his musing after watching “Look and See.”