Climate neutrality goal could benefit the Meadville economy

U.S. Department of Agriculture lacks classification for local foods

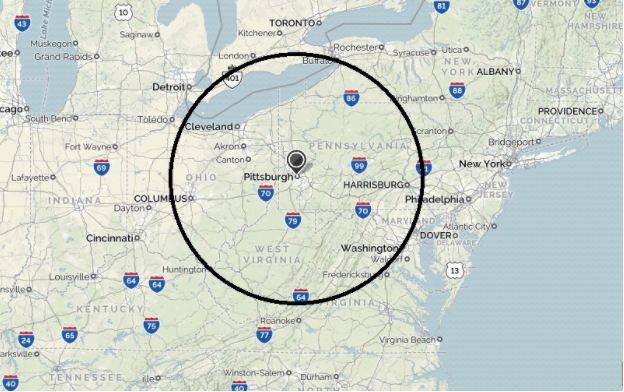

A 150-mile radius, which is indicated by the black circle, is the area that Parkhurst considers local in terms of the food it sources for Allegheny College. As part of its goal to achieve climate neutrality by the year 2020, the college has made an agreement with Parkhurst Dining Services that at least 20 to 30 percent of the food it provides to the college will be locally grown, according to Sustainability Coordinator Kelly Boulton.

Davenport Fruit Farms, located in Meadville, Pennsylvania, is host to rows upon rows of apple orchards, pear trees and more. As the apples of various kinds fall from the trees and break, bees are drawn into the area and buzz around the sweet fruits. Davenport generally ends each season with a harvest substantial enough that it requires volunteers to help bring it in.

These volunteers generally come from Allegheny College, which lies less than five miles away. Davenport, which often sells locally, is Allegheny’s main provider of apples and pears when they are in season.

“The apple crop is very seasonal; it’s a fall product. It comes on in September through October, sometimes into the first week of November, but … we’ll be pretty much lined up to be done at the end of [October],” Jeff Davenport, one of the owners, said.

Davenport Fruit Farms is a family-owned business that has been partnered with the college for close to nine years, Davenport said. The farm is largely reliant on the volunteers the club Edible Allegheny organizes to complete its harvest.

“Without [Allegheny], we really would have a difficult time getting all the fruit in,” Davenport said.

While Davenport Fruit Farms is less than five miles away from the college, it is not clear how much of the rest of the food Allegheny serves is from the Meadville or Crawford County area.

As part of its goal to achieve climate neutrality by the year 2020, Allegheny College has made an agreement with Parkhurst Dining Services, its contracted food provider, that at least 20 to 30 percent of the food it provides to the college will be locally grown, according to Kelly Boulton, Allegheny’s sustainability coordinator. This cuts back on the carbon emissions of transporting the foods long distances to the college.

Boulton said the variables in the percentage of local foods comes from what is available and when for Parkhurst, as well as student demand and the menus Parkhurst creates. According to a graph supplied by Grace Hoyer, Parkhurst’s public relations manager, Parkhurst supplied the college with 17 percent of locally grown foods in 2015.

Achieving climate neutrality would mean the college has no carbon footprint, or that it is not creating more harm for the environment than good. Boulton said the college has a mandatory “greenhouse gas inventory” it is required by the Environmental Protection Agency to calculate, including some items that the college must measure and some items the college can report if it sochooses. Boulton said some of the mandatory items include heating, wastewater, electricity and travel that the college funds. How much local food is served on campus would be an optional item that the college chooses to report.

Boulton said she has calculated the percentage of foods considered local by Parkhurst that are being supplied to the college, but that it would be challenging to calculate exactly how much of that is within the Crawford County area.

Boulton said measuring the carbon footprint from food production specifically at the college would be a “massive undertaking,” and that the college has not been able to collect a measurement. She said she has recommended that there be a junior seminar class recording the food on each order and determining its origins, but so far no such seminar has been created.

Environmental science junior seminars at Allegheny College typically pick one issue the class would like to focus on during the course of the seminar, usually something local to the college, Meadville or Crawford County, and the students apply their studies to come up with ways improve the issue.

Hoyer said Parkhurst has been working to buy locally since 2002.

“We have a program called FarmSource … and basically through FarmSource, we work with more than 250 farmers and producers always within a 150-miles radius of our location,” Hoyer said.

According to Bill Watts, the general manager of the Meadville branch of Parkhurst, most of the fresh and locally grown food Parkhurst receives and distributes is from Paragon Foods, a Pittsburgh-based food distributor. The foods change somewhat seasonally depending on what Paragon’s providers can supply. Because Paragon strives to serve “hyper-fresh” foods, it sources much of its food locally as well.

According to the Paragon website, the company is a “distributor of fresh and specialty foods to the restaurant and foodservice industry in Western Pennsylvania. … In addition to fresh produce, Paragon provides premium quality dairy, fresh meats, seafood and epicurean products to restaurants, hospitals, universities and K-12 schools, clubs and corporate dining clients throughout Western Pennsylvania, Eastern Ohio and Northern West Virginia.”

Parkhurst’s main office is in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and Watts said that food is considered local if it comes from a certain distance from that location. Hoyer said anything from within 150 miles of the Pittsburgh office is considered local.

The United States Department of Agriculture website claims it considers local food “preferably” anything within a 200 mile radius of Washington D.C., where its main office is located. In a 2008 USA Today article titled “‘Locally grown’ food sounds great, but what does it mean?” a Hartman Group Study was cited as finding that 50 percent of consumers “defined local as within 100 miles.” Hartman Group monitors and studies trends in the food and beverage industry.

There is no consensus on exactly what distance is considered local. According to the same USA Today article, there are “no regulations specifying what locally grown means.”

Meadville, Pennsylvania is within 150 miles of Pittsburgh, as is Erie, Pennsylvania. To put in perspective, Pennsylvania’s geographic length is 170 miles, north to south. 150 miles spans most of the geographic vertical length of the state of Pennsylvania.

Because of this wide radius that Parkhurst draws from, Watts said it would be difficult to determine how much food served at the college is actually grown in Meadville or Crawford County.

Just as disputed as how far “local” food can come from is whether “local” is determined by where the food is grown, processed or purchase within whatever distance an organization determines. Because there is no consensus on what it means for something to be local, food can be called local if it is sold locally to a consumer, even if it is grown by a producer 1,000 miles away.

Because Parkhurst sources its food from within 150 miles of Pittsburgh, there is a greater economic benefit on communities within that radius than there would be if foods were sourced from elsewhere.

According to Watts, Parkhurst determines where it will purchase its foods from based on several different factors. One of these is the level of liability insurance a farmer might have. This liability insurance would help cover Parkhurst’s costs in any lawsuits if the farms they purchased from got a consumer sick.

“The small farmers have trouble purchasing the insurance,” Watts said.

Watts said Parkhurst sends a representative to potential producers to inspect the farm and make sure everything seems to be handled in an appropriate fashion.

Some of the food Parkhurst provides is from producers close to Meadville. According to Watts, the college purchases donuts from a provider in Edinboro, Pennsylvania and pumpkins from Al’s Melons, which sells on Conneaut Lake Road, a few miles from campus.

Boulton said she would consider the distance Parkhurst draws on to be “regional” rather than local.

“[It] is still better than buying apples from New Zealand. It makes a lot more sense that we’re buying apples from Davenport, which is just down the road, or some place that’s a little bit more local once Davenport is done with their harvest,” Boulton said.

Boulton said that it would also require a full study to measure what the economic impact on the community is when sourcing local foods, but some larger studies have suggested that buying locally benefits communities economically.

“You’re supporting individual families, you’re supporting the community and then I think more on the Parkhurst scale, I think it certainly has an impact of supporting larger companies like Turner Dairy, where we get all of our milk, and that’s a regional dairy that also has better practices than some of the other larger milk [companies,]” Boulton said.

Supporting local farmers and creating a greater market for fresh foods could make improvements in an economy like Meadville’s. According to city-data.com, the city currently has an unemployment rate of 12.2 percent while the state and national averages hovered between 7.3 and 7.9 percent, according to 2010 census data. The median household income was $28,052 despite the state and national median of about $50,000. The federal government sets the poverty line for a family of four at $24,300.

Two farmers in an article published by The Campus newspaper in October 2016 agreed that “using farming as a sole source of income can be difficult” because of not having the equipment to freeze the vegetables and sell them throughout the winter. The article reported that Meadville and Crawford County have plenty of farmers and fresh food, but they did not always know how to get their products into the market.

Creating a greater market, however, could increase family incomes, and in turn lower the Meadville unemployment rate. Boulton said that the college working to serve local foods makes sense for both the community and the college.

“In the general sense of things is if you’re buying locally, you know what community you’re supporting. … We have all these local farmers in our region. We should be supporting them because we’re [Allegheny] a perfect market for them to sell to,” Boulton said.

Although Boulton could not provide specifics, she believes that an increased emphasis in the community and at the college on local foods has the potential to help the Meadville economy.

“[There has been] more emphasis that has been put on local foods not just from the college but from the community in general [by] reviving the farmers market on Saturday and getting more and more farmers involved. … Now we have lots of local businesses downtown, from local bakeries to a guy who makes salsa and grows mushrooms. So once it’s demonstrated that there is a market, there can be more people coming forward and providing products,” Boulton said.