Icelandic alumna shares experience as medical translator

Helga Edwald, ’83, and her two children, Victoria and Thor, speak to a crowd of students about her experience as a translator and Allegheny student at Grounds For Change on Thursday, Sept. 29, 2016.

Translating a thought—any thought—between two languages takes skill and practice. Translating among multiple languages, more so. But translating the experience of moving between two languages, two cultures, two modes of thinking, is a feat that takes a special kind of communicative clarity.

It was this feat that Allegheny’s only Icelandic alumna, Helga Edwald, ’83, accomplished during her brief visit this Thursday, Sept. 29, in an informal meet-and-greet in the student-run coffee shop Grounds for Change. Edwald, accompanied by her two children, Victoria and Thor, sat down with a group of Allegheny students to discuss her experience as a medical translator.

“In Iceland, we start learning English at a young age,” Edwald said. “We start learning Nordic languages at eight or nine years old. Then, in college, everyone has to take what we call a third language, which is a fourth if you count Icelandic.”

Edwald said that learning multiple languages is not just about the art of communication. A wide repertoire expands the way you think.

“When you learn another language … you learn the culture,” Edwald said. “Every language has a different way of expressing things. You have different ideas in languages that you could not express in your own.”

Edwald first came to Allegheny after graduating from Hamrahlid College in Iceland. Intending to further her studies in English, Edwald fell in love with science and graduated with a degree in environmental science. She returned to Iceland and pursued a one-year teaching certificate in education.

Her next calling was a position at the Nature Conservation Council—now the Environmental Protection Agency—as an editor of a newsletter.

“After that, I changed careers,” Edwald said. “I went to medical school, then worked as a doctor in Iceland and then started a family. And that’s when I got into translation.”

Edwald entered the field of medical translation, and began working for the European Union, translating information for doctors, patients and pharmaceutical companies.

During her time at Allegheny, Edwald made friends with other members of the international community, which consisted of about 25 students. Edwald said that she still keeps in close contact with many of the friends she made back then.

“That was one of the strengths of Allegheny: I got to meet people from different races, different relations, from different countries, and [that] gives you a sense of understanding different cultures,” said Edwald. “It gives you a lot of good ground for the future. Getting to know different cultures is important for all of us. We are all people.”

Edwald herself speaks Icelandic, English, Danish, Norwegian and Swedish. She used to speak German, but said she has not used it for a long time.

Medical translation was at first a side job for Edwald, but she was able to turn it into a full-time career from her experience as a translator and a physician. In her work, Edwald translates medical information for pharmaceutical companies hoping to register new medicines within the European Union.

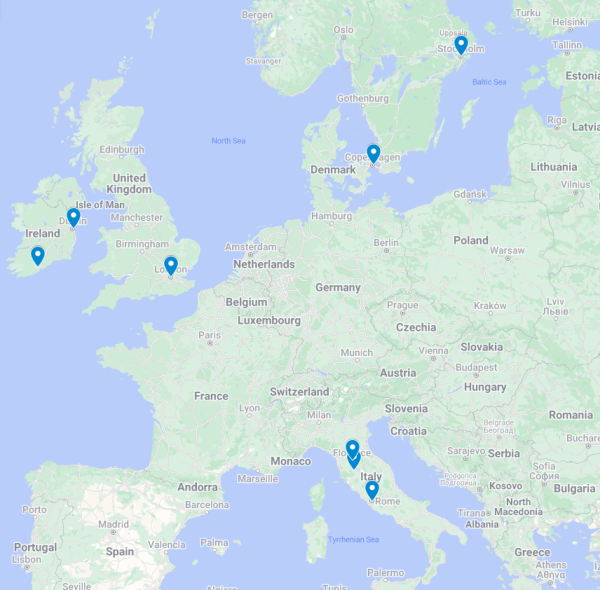

“In Europe, when you register a new medicine, it has to be centralized and registered in 24 countries and languages at the same time,” Edwald said. “Every country in Europe has a different language. … It does not matter if you are a natural science or a doctor, you are always doing something with these languages.”

Because Edwald works independently, she gets to design her own shift. The experience can be isolating and demands a degree of discipline. Translators often do not get the experience of traveling as much as interpreters do, according to Edwald. Still, she enjoys the freedom that comes with independent work.

“Translation is not just taking something in one language and putting it into another,” Edwald said. “It is taking it in, understanding it and expressing it in a different language and a different culture. People in one culture may think differently [from] people in another.”

Edwald’s desire to bridge her skills in the humanities and her knowledge in the natural sciences began some time during her career for the NCC. She began to think about the relationship between people and their environment, and began to consider natural sciences and medicine—to use an Icelandic idiom—two branches of the same tree.

“I have always been interested in people and in culture,” Edwald said. “In medicine, you are using science, but it also involves the art of interacting with people.”

The fact that Meadville’s climate is different from Iceland’s may have helped pique Edwald’s interest in the environment. According to Edwald, Iceland never gets as cold as Meadville, but it never gets as warm as the summers either—in other words, Meadville has more extreme climates. Iceland seems to be windier, however, which became apparent to Edwald and her family during their trip back to Meadville.

“We had pouring rain, and we were walking with umbrellas, and my son said, ‘This is wonderful—the rain is vertical.’” Edwald said.

In terms of snow—the hallmark of Meadville, which sits in the dumping grounds of Erie’s lake effect weather—Iceland seems to have lost its pace against Meadville.

“The snow differs between years [in Iceland],” Edwald said. “When I was younger, we had lots of snow. But now we have more rain than snow. We are feeling that the climate is getting warmer.”

Having grown up in Iceland, both of Edwald’s children are multilingual. At the GFC event, both weighed in on the difficulties of mastering multiple languages. Victoria, who had spent ten months in a French high school in Brittany, France, as an exchange student, said that she felt it became easier to pick up new languages once she had an established repertoire.

“When you are young, it’s easier to pick up a new one,” Victoria said. “So being 18 and speaking three languages already, I felt that French was relatively easy.”

Thor agreed, and said that the trick to learning multiple languages is not just to know how a word translates in and out of different languages, but to understand the relationship between those translations—in other words, between words of a different language.

“You expand your mind—you expand the way you think—when you learn another language,” Helga said.

And that expansion involves more than conscious thought, according to Victoria and Thor.

“Our father lives in Norway, and I speak Norwegian to everyone there,” Thor said. “After about a week, I will start thinking in Norwegian.”

Victoria added that she often dreams in Norwegian as well as Icelandic.

“When you get to the point when you don’t have to think before every sentence, that’s when you know you have a handle on it—when you don’t have to think about thinking in another language,” Thor said. “You just are.”

Victoria graduated college in Iceland this past spring. She triple majored in natural sciences, linguistics and social sciences. She plans on pursuing University programs in animal behavior. Thor, five years younger than Victoria, is interested in natural sciences, and wants to study physics or astronomy.

As she neared the end of her talk, Helga recalled that when Thor was learning Norwegian and Icelandic in Norway, he was forming sentences with words from both languages.

“The teacher at preschool gave me a book on bilingual children,” Edwald said. “It said that as soon as children start putting together sentences with elements from two different languages, and as long as the words made sense, that was a sign that they had captured both languages. … That’s how the brain does it.”

When asked which language they prefer reading in for leisure, both Victoria and Thor agreed that reading a book in its original language beats reading a translation.

“There are so many things that you can’t translate in a language, such as jokes,” Thor said. “There are many jokes in English that I can’t say in Icelandic—they just don’t work.”

On the following day, Friday, Sept. 30, Helga addressed an environmental science class on the topic of geopolitics in Iceland. Victoria and Thor again accompanied her, sitting among Allegheny students.

She began by showing a map of the ages of different bedrocks in Iceland. The youngest was a strip that ran southwest-northeast through the country, at less than 0.8 million years old.

“We have more than 200 volcanos located within the active volcanic zone, and at least 30 of them have erupted since the country was settled,” Helga said. “This is actually where the mid-Atlantic ridge sits under Iceland.”

According to Edwald’s data, nine out of every 10 households in Iceland use geothermal energy. Of all geothermal energy used in the country, 43 percent is used for space heating, 40 percent is used for electricity generation and 4 percent is used to heat swimming pools.

“We have swimming pools in almost every town in Iceland,” Edwald said. “And because they’re so warm, they are used all year round, no matter what the weather’s like.”

In 1970, over 50 percent of space heating in Iceland was fueled by fossil fuels, Edwald said. Today, that number is down to about one percent, mostly concentrated in islands off the coast that are not connected to the national grid. Currently, geothermal energy facilities generate nearly a quarter of the country’s electricity. The rest comes largely from hydroelectric facilities.

Edwald then discussed the Icelandic government’s “master plan for nature protection and energy utilization.” According to Edwald, on Jan. 14, 2013, the Icelandic parliament passed a proposal on a plan to better consider the use and construction of power plants in Iceland. In the framework of the plan, before power plants are built, their environmental impact is assessed. The plant projects are either deemed fit for constructed, cancelled or put on hold due to lack of data.

“Geothermal energy is a renewable resource, but must be used in a sustainable manner rather than in an excessive manner,” Edwald said. “The stepwise development of geothermal resources … creates a frame for sustainable development, and makes sure the resources are still there in the long run.”

Claude-Michel Laurent • Jul 29, 2019 at 4:09 pm

Hi Helga!

So nice reading about what you’ve been doing since 1982.

One of the many international students from back then,

Claude-Michel