I’m currently studying in Cairo, Egypt at American University in Cairo (AUC) and living i

n the Zamalek neighborhood, about 2 km from downtown Cairo and Tahrir Square. I came to Cairo because I thought it would be an adventure. I was on my way back into Cairo from a weekend trip when the protests began and was dropped off downtown by the bus around sunset.

I was completely surprised by the amount of riot police on the streets. On my way back to Zamalek I saw the police had barricaded the road to Tahrir Square.

The next day some friends who were staying in a hostel in Tahrir uploaded a video and I was stunned at the amount of people who had been in the square. Between the 25th and the 28th I did not attend any protests but only heard secondhand accounts of how numbers were growing and the police were becoming more violent.

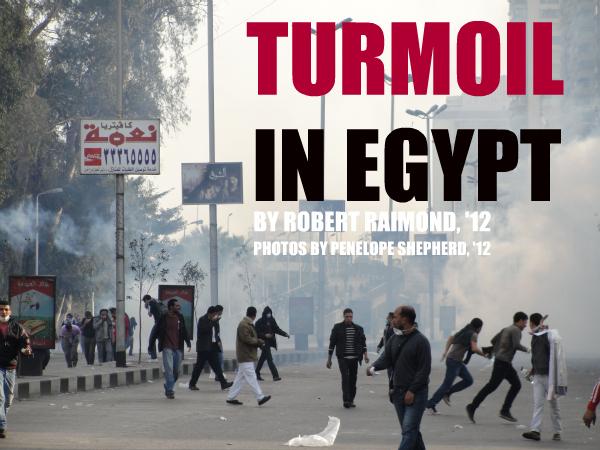

On Friday the 28th, phone and Internet service was turned off. After prayers, an enormous amount of people took to the streets, and the police attacked the protesters. I could feel the burn of tear gas being fired from the other side of the

Nile from the balcony of my apartment. Although some of my fellow American study abroad students went to join the protests actively, I believe that it is not our duty as Americans to intervene with Egyptian affairs. Instead, I went into areas where police were tear gassing to offer water, soda, and vinegar to help stave off the effects of the gas, and first aid.

I was about 100 meters from the police when a woman grabbed me by the arm and said, “It’s time to go. The police are using violence.”

After dark I went out again. When I got to the Nile, I could see a building engulfed in flames and later discovered that it was the ruling party’s headquarters. I started to walk over the 6th October Bridge and I could see bloody bandages all over the place.

There was dried blood on the street and sidewalk. As I walked further down I saw several police vans on fire and people looting from the National Democratic Party building. A man stopped me and said, “Sorry sorry [for the chaos], but we must take our freedom.”

I will never forget that moment as long as I live, watching these people who were willing to risk life and limb for basic freedoms. Soon after I arrived, the Army began rolling in.

People cheered, believing that they were now safe from the police.

After that, there were no police on the streets for about a week. Each neighborhood formed watch committees to protect their property from looters. For the first two nights, there was near-continuous gunfire between our watch and the looters.

But within a few days the looters were arrested and some were exposed to be police officers. That weekend, non-emergency U.S. Embassy staff were pulled from the country, evacuation flights began and the curfew started and AUC suspended classes and suggested that students go home. We actually had a hard time getting food that weekend.

People were buying everything they could, including all the bread and cigarettes in Cairo.

After the 28th I went to downtown Cairo and Tahrir square only twice more. I went to the Million Man March, and the atmosphere had drastically changed from Friday. It was much safer and much happier, almost like a carnival. People had brought their children.

Several people thanked me for my support, and one protester even gave me an Egyptian flag. There was a small group of expatriates that were offering their support. They held a sign reading “One Common Goal: End a Corrupt Regime.” The next time I went, however, pro-Mubarak supporters began fighting with anti-Mubarak supporters. I unfortunately crossed the bridge that the Mubarak supporters were on, and when I reached them, several men began harassing us about having a camera.

Eventually, a man in a suit came up to us and identified himself as a member of the army, telling us that it was unsafe for foreigners to be at the rally and that we had to leave. He then escorted us to a taxi and ordered the driver to take us home. After that night there was a very xenophobic feel. The next day some Egyptians, Americans and I went to a small café in Dokki, outside of Zamalek. After a while, several patrons started saying that they should call the Army or the neighborhood watch to check our I.D.’s because we could be journalists or Israeli Spies.

State television had been saying that journalists and Israeli spies were to blame for much of the violence in Egypt. Luckily, my friends were able to sort it out with them.

Other than the occasional brush with adventure, life here has been pretty mundane, thanks in large part to a rather strict curfew and a blackout of communications. Last week, most of the American students returned home. From what I’ve seen, there is only a handful left.

We didn’t have Internet access for a few days, so we mostly sat around the TV watching the news and would eventually make our way to the hotel bar across the street to do the same. For a while, most shops were closed, as were banks and ATMs. After a few days, though, some stores opened up, and when the curfew was relaxed, and several others did, too.

Now it seems as if life is returning to normal in Zamalek and across Cairo. I was able to see the pyramids from a distance, the Internet and phones are on, classes are starting, stores are stocked with bread and cigarettes and the police are back on the streets to replace the neighborhood watches.

I feel very safe here and have felt very safe for most of my stay. The times I did not feel safe can be chalked up to my own decisions. I can definitely say I would not trade the experiences I’ve had or the people I’ve met here for anything in the world. It’s been amazing to witness, and at times be a part of, history.