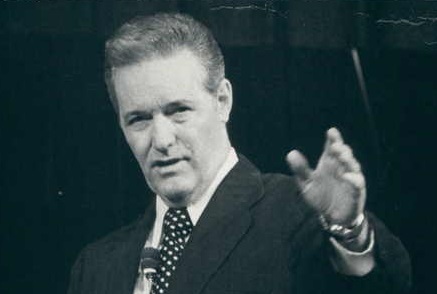

In the thirteenth edition of the 83rd volume of The Campus, one article made the front headline. “Students Vote Apology for Revival Disturbance.” Underneath it is two more stories. “Humbard Wants Apology” alongside “Rex Humbard, Revival Preacher Holds Meeting in Field House.”

In the span of a week, Allegheny College witnessed an event so interesting it required three stories in one edition. The situation held so much attention that, including Letters To The Editors, took over almost five pages of the newspaper itself. The question lingered: what had happened to cause such an outcry on campus?

On Monday, Feb. 22, 1960, Allegheny College was the location of a revivalist service for famous Ohioan televangelist Rex Humbard. According to The Campus, the televangelist’s team had booked the David Meade Field House under the guise of “a quartet” performance. While Humbard did bring along the Weatherford Quartet to Meadville with him, there was no mention that the quartet would be a part of a revivalist service. The college, alongside the public, allegedly only found out about the revivalist service when they saw it in the paper “nine days prior to the date set for the rally.”

Immediately, the college did its best to correct the situation at hand. However, Chaplain Charles Ketcham was told that “the Cathedral organization had already made video tapes advertising the affair, and, according to Mr. Humbard, it would have cost his organization $1,500 to change these tapes.” Though the college did not want to host a revivalist service, there was nothing that could be done: the advertisements had gone out.

Allegheny students did not share the same stance as the college. While the college’s position was to show Humbard respect, it became clear that students did not plan to follow the college’s wishes. Students planned to cause “trouble.” As The Campus reported, “Before and during the program students played cards, knit, studied, or sat watching and waiting. Signs appeared in one corner of the student audience with such remarks as “Oh, Lawd, I’m for Zen,” “Hallelujah,” “Barf,” “Unfair to Organized Atheists,” and “I’m a sinner. So what?” During Humbard’s service, “a cross with fire crackers exploding from it was seen burning on a bluff outside the field house” as a way to mimic Humbard’s renowned use of fireworks in his program.

Allegheny students were not the only audience, however. Humbard’s service was open to the public, and Meadville residents were more of a fan than many students. As the rally ended, The Campus reported a woman running up to the microphone, saying, “I came sixteen miles and brought my children here, and I am thoroughly ashamed.”

Meadville residents were in uproar, disgusted at the way students treated Humbard. The Campus does not report specific public opinions, except for Letters to the Editor from alumni and students alike, but there is an overwhelming assumption that Allegheny College’s relationship with some Meadville residents was tainted by student reactions to Humbard.

In response to the backlash, the Allegheny Student Government voted to release a public apology. Then-President Lawrence Pelletier, who had attended the meeting, expressed that students had done the “very opposite” of what their actions at the rally intended to do: express discontent with a religion with which “many of us cannot agree.”

Nevertheless, Pelletier spoke out against the way that students acted, saying that it was not gentlemanly or ladylike. While the student body voted to release the public apology, they wanted to make it clear that the apology was to those in public attendance, not to Humbard himself. The apology ends, “Although we cannot support the religious views expressed during the service, we realize that our actions were intolerant and wish to extend, our apologies to those in attendance.”

Humbard was not happy with any apologies that the college community tried to give. As reported by The Campus, Humbard felt as though “the disturbance Monday was planned, and that either the president, the dean, the Chaplain, and the faculty or the students authored the plot.”

Allegedly, Humbard felt only one thing could make the situation right: if he was allowed to return to the college and host another revival service with no disruption. If the college agreed to do this, Humbard would “consider that the students were responsible for the ‘plot.’” According to Allegheny’s public relations officer, Pelletier would (most likely) only respond if and when Humbard contacted college officials. Humbard did make a return visit to Meadville, but not through the college. As reported in the March 4, 1960, edition of the Campus, Humbard was returning to preach on March 7 at the Joyland Rollerdome.

This incident made such an impact in 1960 that Rex Humbard made The Campus’ April Fools issue, then called The Hemlock Cup. Humbard is featured in a story about a brawl with Allegheny’s Air Force Cadets. In this story, he is jokingly named the dean of students. In another story, Humbard is jokingly told to be holding a mass meeting for all male students that night at 11 p.m. in regards to the ‘Air Farce’ (Air Force). The last line of the article states, “Rex Humbard will also speak on ‘How to be a Martyr in Five Easy Steps,’ for the battle-minded cadet.”