In the ’80s, research on HIV was at an all-time high, including research into other bacteria like Haemophilus ducreyi that help facilitate the virus. According to the National Library of Medicine, this HIV-focused era fizzled out with the popularization of functional treatments. With less interest in HIV, interest in the very niche and treatable H. ducreyi no longer garnered the attention of researchers. Here at Allegheny College Professor of Biology, Biochemistry, and Global Health Studies Tricia Humphreys and her students are trying to change that.

In the most recent edition of the Karl W. Weiss ’87 Faculty Lecture Series on Feb. 7, Humphreys presented the fundamentals of the scientific paper she authored that is currently in review to be published.

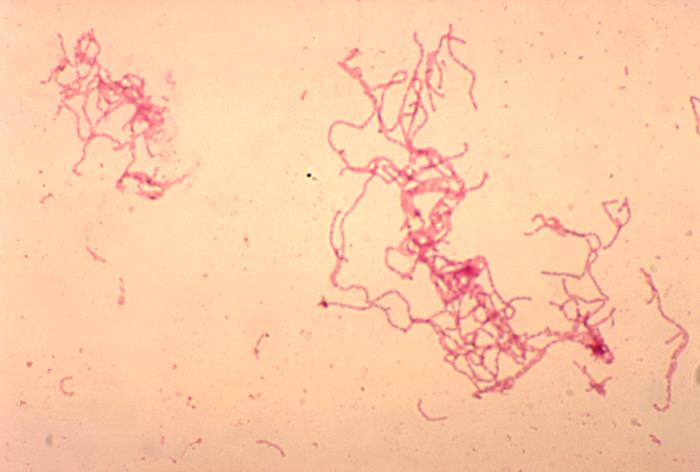

H. ducreyi is most known for its Chancroid variant, a sexually transmitted disease that raises one’s risk of contracting HIV. In the 1980s, this made it a hot topic to research because of the HIV/AIDS epidemic and lack of information about the logistics of this disease. In recent years it has seen more attention for the nonsexually transmittable variant of cutaneous ulcers that are becoming increasingly common in children located around the equator.

The first of the research done in Humphreys’ lab has to do with alternative treatments for H. ducreyi. In research that has already garnered some attention, Humphreys’ students tested different essential oils against the bacteria’s growth in hopes of finding a more affordable treatment for the bacteria.

To make this potential treatment even more accessible, the students did not use any niche lab equipment. Instead, they opted to use common household appliances like blenders. Overall, clove, thyme and cinnamon proved able to significantly inhibit H. ducreyi. These natural treatments were also effective against antibiotic-resistant strains of the infection.

Not quite done with their research, students began to test Resveratrol, a compound commonly found in peanuts, cranberries and products derived from grapes like juice or wine. It is a known antioxidant — meaning it could help your body resist aging and cancer, and has a whole slew of other health benefits. Resveratrol was promising in its ability to kill H. ducreyi, but for a treatment to make it off the ground, it would need to be assured not to attack the “good” bacteria in one’s body.

The lab team set out to learn more by testing it against both H. ducreyi and Lactobacillus. Lactobacillus is found in many “probiotics” like yogurt and it is also the most prominent component of human vaginal flora. Resveratrol’s goal was to kill the bad bacteria (H. ducreyi) but not the good bacteria (Lactobacillus). In every test using this compound, there was a significant elimination of H. ducreyi whereas Lactobacillus was left relatively unharmed, which supports the validity and safety of Resveratrol as a potential treatment.

The bulk of the presentation, however, was about their research into how the disease spreads. H. ducreyi was largely considered an STD, until the non-sexually transmitted variant was rediscovered in 2014 as part of a a global campaign to eradicate Yaws. Often characterized by the same large ulcers found in this new variant of H. ducreyi, Yaws is a skin infection found in very similar parts of the world. The sores that were found primarily on the legs of children were not successfully cured by the Yaws treatment, so the wounds were tested. Many of them were found to contain H. ducreyi bacteria as well as Yaws.

For years, no one knew the connection between H. ducreyi and Yaws until pictures of the children’s ulcers were examined more closely. Many of the photos showed flies swarming the wounds. This led Humphreys’ lab to hypothesize that the flies could be transporting this bacteria into the cuts of kids with Yaws infections while playing outside.

To find out if this was feasible, they planned a series of experiments that started with consulting an entomologist local to the affected area. They identified that the flies involved could be one of three species, one of them being houseflies.

To see if the flies could be the vehicle for H. ducreyi, the team spent weeks raising housefly larvae in the lab. Once these flies were mature, they were left in closed tubes with a cotton ball covered in trace amounts of H. ducreyi. The houseflies were extremely hesitant at first to touch the cotton ball, but when hungry and prompted with food, they would briefly land on it. After landing, the flies were prompted to land on petri dishes. After allowing the dishes to incubate, they were measured to test whether or not the flies could carry the bacteria. Canada’s Health Safety department says that H. ducreyi can only last for short increments outside of very sterile lab circumstances, but the experiments found that flies were able to transport viable bacteria for more than an hour.

Despite being only one of two teams in America currently researching H.ducreyi, Humphreys said she and her students are making leaps in increasing our understanding of this bacteria.

Categories:

Humphreys gives Weiss lecture on H. ducreyi

Story continues below advertisement

0

More to Discover