Dozens of student researchers with the office of Undergraduate Research, Scholarship, and Creative Activities gathered in the Henderson Campus Center around midday on Monday, Aug. 28, to celebrate their work over the summer. The event highlighted not only the academic arguments made during the last few months, but also the connections made between the college and the broader Meadville community.

The symposium opened with an address from Meadville Mayor Jaime Kinder, who pitched community research as a way to build connections between the town and the college on the hill.

“I was really excited to know that you guys were in my city all summer long, doing research that hopefully comes to my desk and we can make change on that,” Kinder said. “We can make Meadville more walkable. We can make Meadville feel safer. We can make Meadville feel like your home — and then we get to keep you for more than four years.”

Of the 53 posters presented at the event, more than half discussed work focused on the college and its surrounding community. Projects ranged from investigations into the history of diversity at Allegheny to work designing websites and mission statements for local nonprofits.

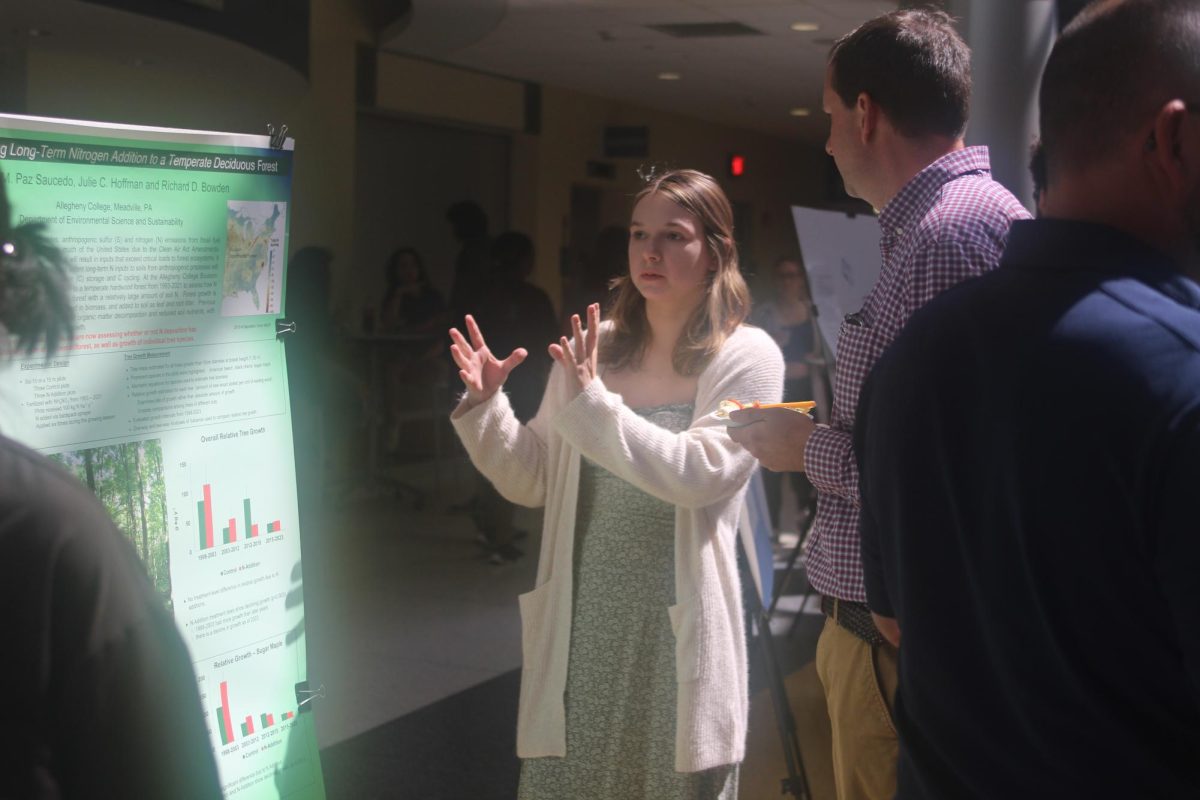

Other scientific work, like that of Julie Hoffman, ’24, and Nathalie Paz Saucedo, ’25, used local resources to examine problems with global ramifications.

Their work — titled “Tree Growth following Long-Term Nitrogen Addition to a Temperate Deciduous Forest” and developed with Professor of Environmental Science and Sustainability Rich Bowden — used a set of plots in the Bousson Experimental Forest to examine the effect of nitrogen on tree growth over a 28-year period.

“We have three control plots and three experiment plots, and on the experiment plots, from 1993 to 2021, they sprayed 100 kilograms of nitrogen per hectare on the plots to mimic how soil would react if you were to put a lot of nitrogen fertilizer over time,” Paz Saucedo said.

The trees were measured using “DBH” — which stands for diameter at breast height, or a measure of the width of the tree at around 1.35 meters or 4.3 feet up the trunk. The biomass of the plots was also measured, but displayed a consistent growth as expected, Paz Saucedo explained.

Overall, the results suggested that increasing the nitrogen levels in soil would slow growth over time, she said. This also varied among species; the experiment monitored beech, black cherry and sugar maple trees, and found that there was a significant slowdown in growth for beech trees.

“Although fertilizer is traditionally used as a growth hormone, we can see, long-term, it does have that effect and that can mean serious implications for the soil on top of all the other soil degrading implications that a fertilizer has,” Paz Saucedo said. “It (the trees) are still cycling carbon, cycling nitrogen, but the crux of that is that there is a slower growth rate,” she said.

Beyond nitrogen-based fertilizers, their research also points to the negative effects of nitrogen emissions from on tree growth. Nitrogen emissions typically come from the burning of fossil fuels in vehicles and power plants, according to the Environmental Protection Agency.

Yet even if those emissions are eliminated, Hoffman said the nitrogen — and its effects — will remain.

“Even if we’re able to totally deal with this, the after effects are still here in the soil,” Hoffman said, adding that additional nitrogen-capture technology would have to be developed and deployed to fully abate the problem.

The research also has connections far beyond northwest Pennsylvania — Hoffman and Paz Saucedo are sharing their findings with researchers in Oregon, Canada, and China.

“China is one of the largest nitrogen emitters, so that’s going to be very interesting to see the results from them,” Hoffman said. “We collaborate with them frequently so it’s really cool for us because we get to see different results from all over the globe.”

When the team stopped fertilizing the plots in 2021, they took samples of the soil and roots and shared them with their partner researchers.

“Since those are PhD candidates working on the samples, they’re able to look at the way, chemically, the soil changes due to the different treatments,” Paz Saucedo said. “We’ve been able to find out how the soil chemistry changes literally thousands and hundreds of thousands of times in the matter of a tiny little sample of soil.”

This, in turn, is helping expand knowledge of the nitrogen and carbon cycles, which run through the soil and plants using and releasing nutrients.

Categories:

URSCA celebrates work from Crawford County to China

Gallery • 3 Photos

Story continues below advertisement

0

More to Discover

About the Contributor

Sami Mirza, Editor-in-Chief

Sami Mirza is a senior from many different places. He is majoring in International Studies with a focus on the Middle East and North Africa and minor in Arabic. This is his fourth year on staff and his second in the EIC position; he has previously worked on News and Features. When not writing, shooting, or editing for The Campus, Sami can be found playing a surprisingly healthy amount of video games, working the graveyard shift at Pelletier Library, and actually doing his homework.