The differences in school openings around the world

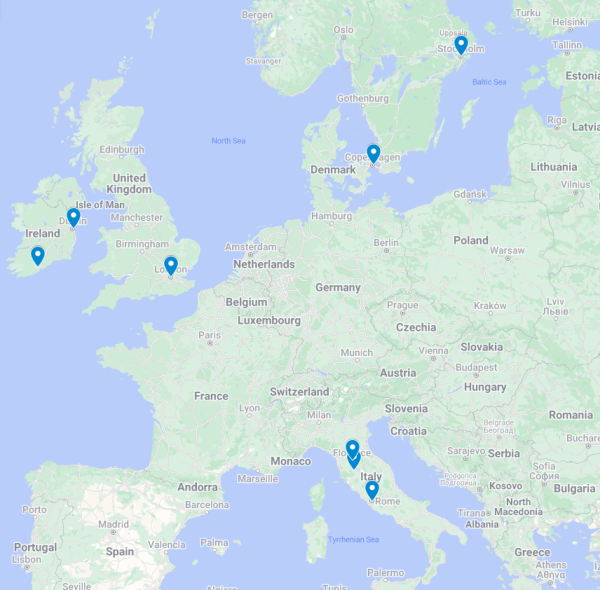

While U.S. schools continue to find their footing amid reopening during a pandemic, many countries have already made attempts at starting in-person education once more. With some plans working, others failing and still more up in the air, a few countries faced challenges.

Ground zero for the pandemic, China — more specifically, the city of Wuhan — was the first to attempt the reopening of schools.

According to an article published by CBS News, after beginning a period of quarantine in January, select groups of students began returning to classrooms in early May. The groups invited back were vocational students and seniors who needed to complete specific work in order to graduate or get into a higher education institution.

Upon entering the building, all students were monitored by a thermal scanner to detect any abnormal body temperatures, and students were required to wear masks and physically distance.

Hong Kong schools also opened around the same time, but ended up closing a week ahead of schedule for the summer in early July, according to an article published by NPR. Students of all ages were allowed to return to their schools, while mask wearing, daily temperature checks and sanitizing surfaces were often required, some students even added more layers of protection in the form of safety glasses. In addition, all students were separated by barriers — most of which were plastic — when it came to meal or snack times.

“I am not [scanning foreheads] for show — I am really doing it to take their temperature,” said principal of Maryknoll Fathers’ Secondary School Lobo Ho in the article. “The more serious your measures, the safer you’ll feel.”

Similar to China, Italy faced COVID-19 before many other countries, but while China worked to contain the virus in schools, Italy was able to adapt China’s protocols and focus on the glaring cultural changes that would have to occur in their country. This comes in the form of the primary Italian greeting being a kiss on the cheek, but lesser known are the more intimate features of an Italian classroom.

According to CNN, many Italian kindergartens and primary schools lack single-student desks in favor of benches and longer tables in order to accommodate more students in a smaller area. The increase in demand for this type of desk across the country led to delayed delivery dates for many schools in need.

Due to the strenuous scenario, school districts have been recruiting citizens to help prepare schools for the upcoming year.

“The hypothesis is to saw the benches, if they are made of wood, or otherwise separate them,” said Adelfio Cardinale, who was recruited by Sicily school districts to spearhead the sawing project, in an interview with CNN. “It’s an extreme solution to solve what is considered the biggest obstacle to overcome on the island.”

In addition to mask-wearing mandates and distancing measures, many schools are seeking to hold classes outside in order to further promote the health and safety of both faculty and students.

Sweden sat on the other side of the spectrum — they neither shut down schools nor went into a national quarantine.

Experts such as Carina King, epidemiologist at the Karolinska Institute, Sweden’s premier medical research center, have expressed annoyance at the lack of research collected during such a unique scenario, according to an article published by Science Magazine.

“It’s really frustrating that we haven’t been able to answer some relatively basic questions on transmission and the role of different interventions, but the lack of funding, time, and previous experience of conducting this sort of research in Sweden has hampered our progress,” King said.

According to an article published by U.S. News, “Only students 16 and older stayed home and did remote learning. Social distancing and masks were recommended but optional, in line with the Swedish government’s emphasis on personal choice.”

The Swedish government expressed the importance of sending young children to school, going so far as threatening to take children from parents in extreme situations if they refused to send students to school, according to Business Insider.

Initially, officials believed following Sweden and a few other nations in reopening schools to children 15 and younger was the correct move.

“In Germany, Denmark, Norway, Sweden and many other countries, schools are open with no problems,” President Donald Trump tweeted.

Experts were skeptical of Trump’s claims, though, and the lack of research done in the aforementioned countries only served to increase concern.

“I’m concerned that there may be a rush to judgment that asymptomatic school children aren’t spreading COVID-19 to adults,” said Anita Cicero, expert in pandemic response policy at Johns Hopkins University’s Bloomberg School of Public Health, in an interview with U.S. News.

With many schools deciding to delay start dates and the lack of government support for individual district reopenings, the U.S. is in a precarious position, according to the New York Times.

In the same article, The New York Times published a graph showing that much of the U.S. should not attempt to reopen, as COVID-19 still poses a significant threat.

Georgia schools became a testing ground for U.S. reopenings when they began in-person classes at the beginning of August. More than 10 schools sent letters warning of a student who had tested positive for COVID-19 after two or three days of classes, according to the New York Times.

According to the article referenced above, Etowah High School in Cherokee County, Georgia was caught in the crossfire, as 260 students were removed from school and quarantined after five days of classes. Educators in the area felt endangered due to growing anti-mask sentiments.

“I hope with everything within my being that no one who gets sick right now dies,” former English teacher Miranda Wicker wrote in a post to a Facebook group composed primarily of concerned educators and parents. “This did not have to happen. This was entirely avoidable.”

Roman Hladio is a senior from Wexford, Pennsylvania. He is studying English with a creative writing emphasis, and completing requirements for a Journalism...