Looking forward while looking back: Campus community reflection on art controversy

The artist said they still have the unnamed triptych that inspired online controversy but have since moved it into storage.

In February of 2019, a student artist stirred conversation and controversy. A year later, the campus community is still partaking in the conversation that began with an image from an art project he and a friend created that displayed the phrase “kill cops.” Allegheny continues to change in response to that conversation.

At the time, the three-paneled piece — a triptych — was originally made to seek inspiration for a class project. The large paintings had been produced in a semi-public wing of the Art Department in the Henderson Campus Center but were not meant to be on display and were considered works in progress. A cropped image of the painting, which contained the phrase “kill cops,” was posted to Facebook. The response to this involved not only the artist, but the college’s administration, public safety officers, students and faculty.

“Things are still healing, I guess,” the artist said. “I think that what (the controversy has) changed is the way I go about discussing my work, and actually just being more prepared to defend it, if anything.”

The artist, reflecting on the events that transpired over a year ago, said that while they feel they and their practice as an artist have moved on, there is “just a lot to be said.”

While many broader changes have taken place that administrative officials point to as improving the college’s ability to respond to such incidents in the future — Executive Vice President Eileen Petula and Dean of Students April Thompson pointed to the January hire of Public Safety Director Jim Basinger — the Art department’s specific response included the placement of signage on doors that enter into the art wing of the campus center. Those signs inform anyone entering the space that it is an area of artistic expression.

“That’s really important, that context,” Provost and Dean of the College Ron Cole said.

Thompson echoed the importance of the plaques, saying that the Art Department has done a “fantastic job” of posting them.

“(The plaques) make clear that there are things that are controversial, and that if there are things that people want to discuss, there are ways to do that,” Thompson said, noting that even as someone familiar with the college and the context of the Art Department, she appreciates the reminders they provide.

Cole said the plaques are part of an effort to help foster a space that still allows for artistic expression.

Cole said the Art Department is and should be open to addressing controversies as they arise.

Chair of the Art Department Amelia Carr expressed similar sentiments.

“Artists have to make that choice for themselves, and some artists, thank goodness, have chosen to be controversial, and call out things, and other artists, you know, have a different approach to that,” Carr said. “The balance needs to be, especially in a teaching environment, creating a way of talking about that and how that’s going to happen.”

In the physical teaching environment of the Allegheny Art Department, Carr said the incident led to a shift in spaces where students work. Students had previously been able to work in the hallways “for years,” where Carr said as far as the Art Department was concerned, that was part of their space.

“We didn’t think it was all that exposed,” Carr said. “Some people even enjoyed seeing student work in progress. That was just a way we did business.”

Carr said that, as a result of the controversy, that status quo made a deliberate shift, and the hallways are now viewed as public spaces. According to Carr, art students are the biggest victims of this shift, as the spaces they are now able to work in are not necessarily sufficient for the creation of their work. However, she added, the compromise allows the Art Department to protect students in their allotted areas.

While the practical change has limited student work space, Carr said she was “gratified” to see one message come out of the controversy: art matters.

“Sometimes it seems like people just ignore art, you know, it’s wallpaper,” Carr said. “I think it reminded us that what we do is visible, and it matters, and it helped bring attention for students especially to the kind of impact their work could have, so they need to be aware that their choices make a difference, and they need to make those choices deliberately.”

The social media outcry also provided some “frightening and very instructive” lessons for the Art Department, according to Carr.

“The stuff that was going on on social media was not in line with our statement of community either — not by a long shot. I’m not sure those people even really cared so much, but just wanted to be online and say threatening things,” Carr said. “It was very instructive as to how quickly something could be taken completely out of context and bring out the worst in people.”

The Facebook-based nature of the response made it, and the lessons the Art Department learned, different from previous controversies, Carr said.

Not all of the changes that have taken place since the initial controversy have taken place within the art wing itself. Cole said that “singularly one of the very important parts” of the changes made at the college recently was Basinger’s hiring.

“Hiring a new director of public safety is a very important step towards building that relationship within our community and external,” Cole said. “One of the things that really appealed to me about our new director is his focus and very strong emphasis on community policing.”

Within the Allegheny community, Basinger said that he feels public safety has a really strong relationship with the administration — one that he is poised to continue by acting as an “advocate” for the public safety staff.

Basinger hopes also to expand that staff, ideally to eventually boost diversity, and has listed job postings online. Once he has hired additional staff, he plans to work with the state police recruiter and the Dean for Institutional Diversity Kristin Dukes to have Diversity and Inclusion Training for officers. He noted that the officers have already received that training, but putting it on again would be a challenge with the current limited staff because officers already struggle to adequately cover shifts. For now, he says he’s enforcing high standards of respect among his officers.

“I’m telling all my officers to be polite and be professional every time you deal with someone — smile, good morning, good afternoon,” Basinger said. “Treat the people you’re working with the same way you want your family to be treated.”

Basinger said he feels that respect is essential, and that communication is as well, especially in situations like the February 2019 art controversy.

He said he first learned of the controversy as it initially happened, since he previously worked with the Meadville Police Department and continues to live in the Meadville community.

“If you just see that (artwork), I could see where that would offend a police officer,” Basinger said. “I think it would be very hard to work (as a public safety officer), not knowing the entire context of what that mural was about.”

Basinger said that he has since learned more about the artist’s work and the context in which it was produced.

“Having it explained to me, the artist was trying to let people know, ‘this is what I see in my community,’ and to bring that to people’s attention,” Basinger said. “Now, I haven’t talked to the artist. I’ve talked to (Cole), and he explained that the artist wanted to bring attention to the fact that that’s the way that people feel in the community where the artist has grown up. That might not be how they feel when they come here to this campus. I would certainly hope they don’t feel that.”

Thompson said she believes Basinger’s presence is helping to boost positive feelings.

“I think the best thing he’s done so far is to build some confidence among our community that we have a leader who we can rely on,” Thompson said.

Basinger said he hopes to continue improving the relationship between public safety and the student body, and that the artist could have been expressing a similar sentiment.

“The person could have actually been advocating to improve relations with police,” Basinger said. “I don’t know. I haven’t talked to them. I know that could be a stretch, but if you’re showing how negative something is, maybe you’re drawing attention to it because you think it needs addressed.”

Something else that needs to be addressed in scenarios like the art controversy is the impact on individual students, according to Thompson. To that end, she said, she created the Associate Dean of Students for Case Management position, currently filled by Jen Foxman.

“Jen Foxman’s role has really enhanced the student experience,” Petula said.

Thompson explained that Foxman’s position, inspired by similar positions she had seen on other campuses, exists to help students to navigate bureaucracy when they come up against crises of various natures, essentially acting as “a campus social worker.”

“It’s not the kind of position that creates programs or anything like that,” Thompson said. “It actually just reaches out to one person to say ‘how can I help you right now?’”

Thompson shared the example of the fallout following the posting of the “kill cops” portion of the triptych. She said that other student artists, student activists and students with police or faculty family were all affected differently. If a similar scenario were to arise, according to Thompson, Foxman would be in a position to help them in whatever ways their unique situation required, even helping them to navigate conversations with parents.

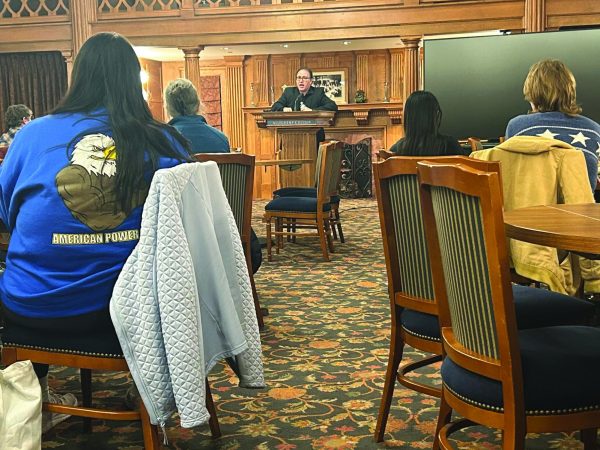

Thompson works not only with students but also oversees public safety. She said the relationship between the two has been navigated, at least in part, through “a lot of listening and talking together,” including through forums for various on-campus groups like students and faculty.

Thompson also said that Basinger, who lived and worked with the Meadville police while working as a Pennsylvania State Trooper, is ideally situated to promote ongoing dialogue with Meadville police — a relationship questioned by the controversy over the artist’s work.

On their Facebook page, Fraternal Order of Police Lodge 97, made up of Meadville city police officers, posted a picture of the entirety of the large triptych, in addition to the cropped image of the “kill cops” portion. On the post, they said that it was “disappointing that (the artwork) was displayed, more disappointing that it took so much outcry for it to actually be removed.”

Lodge 97 has in past years held an annual country western-style concert at Allegheny in the spring. Director of Conference and Event Services Lynn McManness-Harlan said in an email on February 26 that the college was notified by Lodge 97 that they will not be hosting the concert this year.

In a statement on their Facebook page on March 6, Lodge 97 announced that “unfortunately due to circumstances outside of our control, we had to stop having our annual Country Western Show at Allegheny College.” The statement announced that they would instead be partnering with local businesses and organizations to put on the Roots and Brew Music Festival, to be headlined by Justin Moore at the Crawford County Fairgrounds on June 6.

Reflecting on the events of the past year, the artist said they were initially taken aback and struggled to understand the response on social media and by the Allegheny administration, stating that their professors and fellow students of varying ideologies and backgrounds understood the space that their work was in.

“That was the difference: the context and relation to that,” the artist said. “It wasn’t seen as a means to create havoc or violence in any sort of sense, actually. It was more of a sense to bring in the viewer to reflect on the simplicity of two words that are intense and that have symbolic influence and also real-life consequence.”

The “kill cops” portion of the work was, the artist said, a way to call attention to a very real issue that has touched their communities — both at home and in Meadville. They questioned what options are left when people seek help from authorities and find themselves ignored or being actively harmed.

“You know where that leads to, and it’s a shame,” the artist said. “It comes from a historical background. There’s a profound catalogue of officers, and not just officers — people in power in general — abusing the disenfranchised. Especially where I’m from, I’m from New York City, and that’s not the only city that has police problems.”

They said abuse of power, particularly as it affects vulnerable populations, is an issue we should all pay attention to, “regardless of where in the world it is.” According to the artist, other students have shared the way they value discussing that issue amidst conflicting opinions in the community.

“I’m not the one living here indefinitely,” the artist said. “I haven’t been here for more than my college career. So who am I to try to stir the pot here or in general? But at the same time, I’ve had other students come up to me and tell me the imperativeness of maintaining this dialogue.”

Ultimately, the words “kill cops,” which he called a “sixth or eighth of the painting,” were a small piece of a larger work, the artist said.

“When I made that piece, that wasn’t the focus of it all, either,” the artist said. “There was so much more going on.”

While that piece was not the artist’s focus, it was the focus of the Facebook and social media conversation that followed and led to, according to the artist, multiple threats on their life.

“It was just more of the worry that there was just going to be one angry person one day walking down the street, and just find me, and I wouldn’t be here, and that’s a real threat, that people said they wanted to lynch me,” the artist said. “They wanted to kill me. It was pretty intense stuff.”

The artist said they spent the first week or so of the social media backlash trying to withdraw from interaction, and was conscious of the threats they had received when they went into Meadville — including while staying on campus over the summer “for financial reasons.”

The artist said the threatening messages they received were not the only thing they found painful about the response to their work.

“It was a little damaging, I think, personally to me, to recognize that there was so much proactiveness in taking that down and to not ruffle any feathers,” the artist said.

The artist pointed to issues like “rapes, racial slurs and… other forms of violence” that they see on Allegheny’s campus but they feel are less connected to financial concerns and not addressed to the same extent. They also pointed to issues that affect the broader Meadville community, like racism, and said they found it “backwards” for that form of violence to be less addressed than work he had produced “in a college campus in a studio space.”

“I think that’s the real reason why I personally felt a little defeated after the whole thing,” the artist said. “I was very sad. I didn’t enjoy any of the process.”

The artist said they also recognized that others were affected by the social media backlash, and expressed their appreciation for the professors they have had in classes.

“They’ve been there for me, most definitely,” the artist said. “From their position, they definitely had to recognize their daily life being disturbed due to that single instance. I recognize the severity of that reality. I was trying to be very considerate and not just lash out and say this was censorship because I care about them.”

The artist said their professors have also brought the incident into the classroom — this semester, one of their professors used it as a discussion point to have a class conversation on self-censorship.

“Even the students themselves were saying we understand the privatized aspect of doing what you want in your own property, however, it’s also pretty complicated in the setting of an academic institution, especially within a department such as the Art Department,” the artist said.

That setting has shifted slightly for the artist, who noted the shift in workspace from the hallways into specific studio areas. They said they were told by the Art Department that the logic behind this decision was that the works posed a fire hazard.

Has any of this held the artist back from artistic expression? Regardless of where it is being made, the artist says their artistic practice continues to progress. They continue to try to move past the idea of a “finished product” that they see as often inhibiting classmates and fellow artists from being entirely honest in “their process of making” in academia. They are focusing on elements like “color theory, texture, taking classical antiquity like from the Renaissance and the lush gold display of the Baroque,” all of which is combined with their “abstract, expressive, heavy, muddled, stylistic approach.” They have displayed their work in two shows in galleries in New York City, where they are from.

And they continue to be open to communication regarding their art.

“I love dialogue,” the artist said. “I think that’s probably at the forefront of all my work, too, is to have people not just look at something and understand it immediately and then walk away, but more along the lines as to look deeply into every part, and to question and to have a conversation.”

That is what the artist would change about the controversy that took Facebook by storm in February of 2019.

“I’d rather see people have a discussion, argue with me even,” the artist said. “Don’t just try to misinform and deter and destroy.”

Cole also expressed his desire for the conversation to move past a singular piece.

“I really want to not focus this on just that one exhibit,” Cole said. “The broader issue here is ways in which social media can be used without context to weaponize messages. That’s what we have to be able to address and talk about.”

Carr said making people talk is part of what makes art, art.

“Controversies in art, you know, that’s the name of the game,” Carr said.

The artist hopes that their art can continue to provide a learning experience.

“If I’m able to stir a controversy that’s nonviolent, just have people thinking and react, that’s far more informative than going out of your way to send a message through violence,” the artist said.

Olivia Blakeslee is a senior majoring in English with a minor in journalism in the public interest. This is her fourth year on staff, and she is serving...