Just do it: encouraging introverts to leave comfort zone

The world is such a rich, vibrant place — if only we open our eyes and tune our ears to its splendor. There is a beauty and cadence to our daily rhythms — seeing the sun peak through our blinds, cajoling us to our 8 a.m., perhaps — probably — begrudgingly; hearing the bells toll at each hour (when they work); that deep breath one takes when your classes for the day end and you can walk at a leisurely — or maybe eager — pace to a bustling Brooks Dining Hall where you wait in the mainline for a surprise smorgasbord, craning your neck to see if there is anything good.

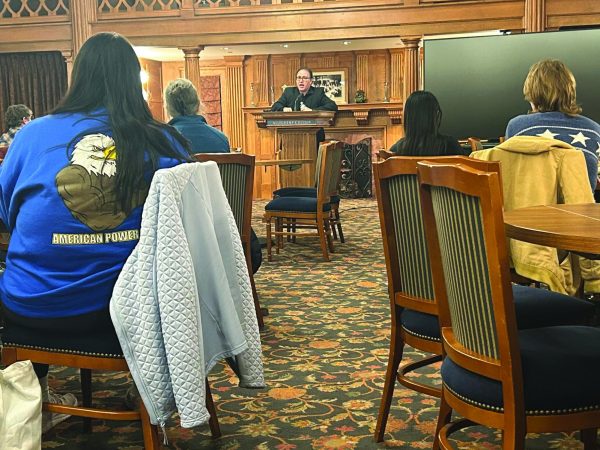

But there is something missing in this description, though it may be implied: other people. Imagine that you were the only one on campus. For those of us who remained at Allegheny for fall break can attest, campus isn’t the same without the people. It lacks life in the same way a full house at a theater feels more “alive” than one with only a sparse spattering of bodies. During Hilary Link’s inauguration as President of the College in late October, she mentioned the fear of the other, something she had to overcome in her six years abroad in Italy. This fear is universal — it has plagued humans for as long as there were other groups of people to fear as we banded together to ensure our survival — wracked by mysteries of the unknown, disturbed to the core by the certainty of constant uncertainty in a dark, unpredictable world. But on the other side of this fear,understandable as it may be, is liberation — boldly embracing that uncertainty and daring to forge ahead anyway, eschewing what Professor Elizabeth Samet from West Point in the same ceremony called “preparation paralysis.” Part of growing up means overcoming this fear of other people, and for students in a recent study conducted by researchers at the University of California, Riverside headed by Sonja Lyubomirsky, the results prove that venturing out into that unknown — in this case, talking to someone you don’t know — can only change your life for the better.

Researchers asked 131 participants to “act introverted” and “act extraverted,” having them alternate between the two each week. But the researchers did not use these labels, so as to reduce bias: instead they instructed the groups, in one week, to be “talkative, spontaneous and assertive,” and in the alternate week, to be “deliberate, quiet and reserved.” To the researchers’ surprise, the introverts among the participants experienced elevated moods during the “extraverted week,” and, even more eye-opening, the introverts reported no ill effects or discomfort with acting this way. But in these descriptions, the real effect of the instructions is that people either remain isolated from others or not. A similar study asked students to talk to other strangers on a train or remain silent — and it produced similar results. Many people who don’t reach out may simply be unpracticed at, and therefore afraid — but these results reveal that, though introverts may need to recharge after social interaction, these traits don’t “belong” to anyone — that talking to strangers is a risk that more often than not feels good that anyone can use to add vibrancy to their life.

In writing this story, I came upon this study and felt compelled to speak. I had the research, but I needed a flesh and blood example: enter Adam Cohen, my co-writer. He came to The Campus meeting inspired, having spoken to some strangers — but not any strangers: Cohen spoke to and interviewed the New York Yankees, his childhood idols.He was desperate to speak to his experience, which started out scary but ended in triumph — but personal experience isn’t sufficiently newsworthy. So I reached out — and offered to write this piece together. In putting our heads together, I knew that he had his source, and I had my story. So together we worked: two strangers who, together, would create something one of us could not do alone. One of my first questions concerned some tactics he used to overcome the pressures of the situation and connect with the Yankee players — he told me about his “pen trick” — and on we went from there, and sooner or later we were laughing and sharing together, though we had just met, already a perfect example of precisely what we set out to prove:

A note from Adam

As Kelley mentioned, the study shows that both introverts and extroverts can experience positive feelings when they reach out, put themselves in uncomfortable environments and talk to strangers. I personally had to overcome a lot of my fears this past year, but by “acting extraverted,” I ended up with a lot of success.

Before arriving at Allegheny this fall, I took a gap year in Israel to play baseball. There, I realized that my dream of becoming a professional baseball player would never happen. I isolated myself for months from my roommates, and watched hours upon hours of television each day. However, I forced myself to practice broadcasting for the Yankees, applied for a writing internship to keep me busy and talked to new people at parties in Israel. The result: I met some of my best friends and made great strides in my journalism career, which allowed me to represent the company Back Sports Page when reporting on the Yankees.

At Yankee Stadium, I saw my childhood heroes everywhere I looked. However, every time I tried asking for an interview, I hesitated —in that split second, some other reporter had talked to them first. After missing five potential interviews, I began to lose hope. Had everything I had learned in Israel meant nothing? Of course not.

The next person I saw I was definitely going to interview. I saw a Toronto Blue Jays player and stood nearby to speak with him. He saw me with a pen and asked if he could use it. Finally, an opportunity to interact with him. After returning the pen, I asked for an interview, and he obliged. I even did the same “pen trick” on another Blue Jays player, and the method worked again.

Kelley mentioned when she interviewed me on her radio show that Canadian clinical psychologist Jordan Peterson urges people to find a purpose to justify their suffering. My “suffering” in Israel — and at Yankee Stadium — was justified because I had amazing experiences when I “acted extraverted.” I understand that most people will not be able to see Israel or Yankee Stadium, but even on campus, anybody can try to put themselves in more social situations. Go sit next to someone from your class with whom you have never hung out before, go talk to the person waiting in the food line and go talk to the person in your hallway you have never had a conversation with. Maybe the stranger you talk to will become a good friend of yours. Even if you get some awkward looks, it is not going to tear you apart. At the very least, feel proud that you are putting yourself out there. There is just one trick to remember: Stop worrying about the outcome, and just do it.

The results

The results of this study, as confirmed by Adam’s experience, suggests that extraverts, though they gain energy by interacting with people, don’t own the attributes assertive or talkative or spontaneous. These qualities are fluid and come with practice. Whether you draw upon the power of the favor as Ben Franklin did when he asked to borrow a book from an opponent, a tactic that drew him near, or the pen trick as Adam did, you have inner resources, and in an increasingly isolated world, you have a moral duty to use them and reach out — to ease your own suffering and those of others. What else are you going to do with you time? I see so many people avoid others and avoid attempts at connection because they are afraid. Well, I’m telling you that there is something marvelous on the other side of that fear: Ability — even if you are just “acting” like you have that ability at first. As Sanford Meisner says, “acting is the reality of doing.” You can only act extraverted to a point until you are just doing it. We all start out in this world as imposters, and we slowly work towards expertise as our experience grows. Push that experience. You’ll feel better, and dare I say, more alive because of it. I’m so glad that I met Adam and that we had the opportunity to work together, and it would not have happened if we stayed silent in our own worlds and never collaborated. This weekend, we’re watching Bojack Horseman Season 6 together. Practice reaching out, speaking as an extravert — and listening like an introvert — and you will have a much more complete experience as a social being, and soon, the “art” of both will become so refined that it will become “nature.” Talk (and listen) to strangers; feel better. Just do it.

Adam Cohen is a third-year student from New York City. This is his second year on the Campus staff and he is a Communication major with a double minor...