Touring the Universe: Lombardi discusses space during lecture

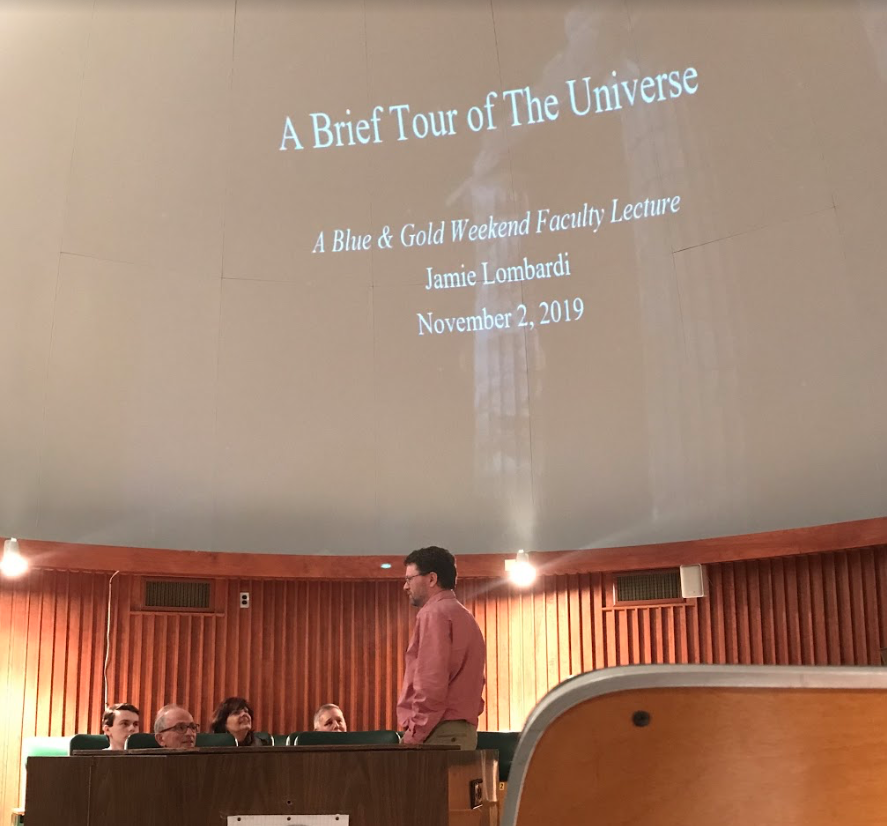

Professor of Physics James C. Lombardi Jr. talks to visiting family members of students before his lecture on Saturday, Nov. 2, 2019, in Wible Planetarium.

As a member of the Allegheny College community, where does one fit into the universe? This question was explored by Chair of the Physics Department and Professor of Physics James C. Lombardi, Jr.

Lombardi gave a lecture titled “A Brief Tour of the Universe” at 4:15 p.m. Saturday, Nov. 2, in the Wible Planetarium, as a part of the faculty lectures event for Blue and Gold Weekend. The lecture focused on how vast the universe is, and showed audience members where they stood as a part of that universe.

Lombardi began with some background information on himself, including that he took his position over from his father, who was also in attendance.

“I’ve taught physics and astronomy here for over 13 years,” Lombardi said. “Before that, my father taught physics here since 1972, when he moved our family here to Meadville, Pennsylvania.”

Lombardi additionally introduced his wife and welcomed everyone to the Meadville community.

A main part of Lombardi’s lecture was shown through pictures and videos of the universe, displayed through the planetarium’s star projector and new digital projector.

“My father taught me how to use the star projector, which has been in essentially constant use for over 50 years,” Lombardi said. “Just recently this year we got a new digital projector on the side to compliment this projector. And they both do different things, and we’re going to use both of them today.”

Lombardi began his lecture with images from the newest space technology, including spacecrafts, focusing first on the sun. He described the two spacecraft that are orbiting the Earth that study the sun and show how the sun is “changing all the time.”

Lombardi then illustrated the vastness of the solar system.

“The sun of course is at the center of the solar system,” Lombardi said. “When we talk about the solar system we’re talking about the sun and all the things that orbit it. There are some things in this depiction that are to scale and some that aren’t. So the sun — you can fit about 100 suns from the sun to the Earth, … you can fit about 109 Earths across the diameter of the sun.”

While describing the distances between planets and formations in the solar system, Lombardi continued to project images and videos onto the domed ceiling of the planetarium, which played out and moved above audience members’ heads.

Lombardi then described the “hundreds of millions of asteroids” that can be found in the asteroid belt in the solar system.

“It’s important for people to study asteroids for many reasons,” Lombardi said. “They give an idea of what the solar system was like at the time that it formed. Another reason is that these asteroids and comets as well, which are ice balls that are mostly out much further in the solar system, are potentially dangerous to us and could cause mass extinction events.”

Lombardi used the extinction of the dinosaurs 65 million years ago as an example. Though the odds of another asteroid hitting the Earth in the present era are slim to none, Lombardi said it would still have catastrophic ramifications if one did, including climate change like the climate change that killed the dinosaurs.

“So it’s worth monitoring these asteroids, and seeing where they’re going and if you need to do something about it,” Lombardi said.

Lombardi explained the process that would occur in the event of asteroids getting too close to the Earth, sometimes so close that they could be seen as a bright light in the sky. According to Lombardi, if an asteroid was that close, the Earth would ideally notice with enough time to deflect it and change its course.

Lombardi then moved away from the asteroids into what he described as variable stars, specifically one called “V838 Monocerotis.”

“The V stands for variable star and the 838 means it’s the 838th variable star in the Monoceros constellation,” Lombardi said. “This particular star is variable because two stars collided, and we were lucky enough with telescopes to catch those collisions in the action.”

Lombardi described how the V838 stars collided multiple times due to not merging right away, and ejected material into space while this process was happening. Additionally as the objects ejected move away from the center, they cool down to become brighter and expand to become more transparent, according to Lombardi. Lombardi used the picture on the screen to show this process and then showed the audience the center of the star which could be seen through telescopes after this process.

Additionally, Lombardi said his research focus is on star collisions, and he focuses on them with his students, which is why V838 “is near and dear to (him).”

After discussing with the audience about the variable stars a bit more, Lombardi moved into galaxies. He began with the Milky Way galaxy, once again displaying a large picture on the projector for the audience.

“It takes about 25,000 years for light from the center of the Milky Way to reach us in our arm of the Milky Way galaxy,” Lombardi said. “That is to say it is 25,000 light years away. A light year is the distance that light travels in a year.

Lombardi explained that light moves so fast that it could travel around the Earth seven times in a second if “you could make it go in a circle.”

“Even at that great speed it would take 100,000 years for light to go from one side of the galaxy all the way over to the other,” Lombardi said.

Lombardi added that the Milky Way galaxy is only about 1,000 light years in thickness, and that the Milky Way fits into the category of galaxies known as spiral galaxies. He then showed more real life pictures of other spiral galaxies in the universe — there are thousands of them.

“So when people tell you things like there are a trillion galaxies in the universe and the universe is big, there are pictures to back that up,” Lombardi said. “It’s not just somebody’s idea of what the universe is.”

Lombardi went into detail about the trillions of galaxies that could be found in the universe, and the hundreds of billions of stars found in each of them, comparing it to sand on the beach.

“Think about going to the beach and laying there in the sand,” Lombardi said. “You pick up a handful of sand and you start counting the grains. Then you look at the beach and you think of all of the dry grains of sand on that beach. And then you think about the entire Earth, and you think about all of the dry grains of sand there are on all of the beaches of the Earth, and then multiply that by 10. That’s how many stars there are in the universe.”

Lombardi added that each star will most likely have its own planet, and therefore there are just as many planets in the universe as well.

After a little bit more information on galaxies, and a pause for questions from the audience, Lombardi called up a volunteer to help show the new projector in the middle of the room. The projector pulled up the stars as a person in Meadville would see them at night in November. It then moved the stars along as the days and months went by. They also changed depending on the latitude that the projector was set at. Lombardi also helped to show this with an animated video clip of astronauts in space, with Elton John’s “Rocketman” as the background music.

“I wanted to give you an astronomy themed song, just to give you some ideas of what this new projector can do,” Lombardi said.

Lombardi concluded by using the projector to show the different constellations and formations of stars during different seasons. These formations included triangles formed by stars that appeared in a certain place during the summer and winter, known as the “summer triangle” and “winter triangle.”

Lombardi discussed the different constellations and stars that formed them, giving his audience a quick quiz at the end.

“So this universe is a very big place in which we live,” Lombardi said. “It’s big in many ways; in the amount of time it’s been around, in the size that it is — and it’s big in terms of the number of things within it.”

Sara Holthouse is a senior from Panama, NY. This is her third year/final semester on staff, where she has previously served as news editor for the past...