‘On the Basis of Sex’: A fun, engaging story with a powerful message

Who was it all for, if not for me?

The powerful question is asked by Jane Ginsburg, played by Cailee Spaeny, in Mimi Leder’s Ruth Bader Ginsburg biopic “On the Basis of Sex.” The film follows Ruth, played by Felicity Jones, as she navigates the challenges of being a woman in a male-dominated law career. Ruth’s frustrations, discouragement and desperation to pursue her dream culminates in a single question from her daughter: Who was it all for, if not for me?

In that moment, Jane represents all girls for whom Ruth had fought and would continue to fight throughout her long career. Jane becomes the hope her mother needs to argue her case and the sincerity the audience needs in a story that centers around the trials of women fighting for gender equality.

Covering over a decade of Ruth’s life, the film opens with the future Supreme Court justice walking amidst a veritable sea of men while a hardy male choir sings a Harvard University song. Ruth enters her first classes as a Harvard University student, and challenges based on her sex immediately present themselves.

Balancing her home life with husband and fellow Harvard University student Martin Ginsburg and her academic studies with professors who refuse to take her seriously, Ruth’s fast-paced life only becomes more demanding when Martin is diagnosed with testicular cancer. Ruth begins attending both her classes and Martin’s, taking care of their young daughter during the rare, quiet moments.

However, her challenges do not stop with graduation.

In remission from cancer, Martin, played by Armie Hammer, graduates from Harvard University and is hired at a law firm in New York City. The Ginsburg family moves to the city, where Ruth, now a Harvard and Columbia University graduate, is denied a job by over 12 law firms. As she grows increasingly desperate, Ruth eventually accepts the position as a professor at Rutgers University.

Although she teaches legal cases, Ruth feels as if she is giving up, buckling beneath the pressures of a system that challenges women more than it does men. Martin offers his unerring support, but he does not fully understand why his wife feels as if she is abandoning her ambitions.

These moments of the film, when Ruth feels she is at her lowest point, show the strength of her marriage. While Martin does not completely grasp the challenges Ruth faces, he is willing to listen to her and learn. In a few scenes that showcase the sometimes tense relationship between Ruth and Jane, Martin acts as the maternal figure toward his daughter, an interesting parallel to the film’s argument that men are able to be primary caretakers of a household. He never dominates a scene, but his quiet strength and constant faith in his wife make him one of the best supporting characters in recent film.

Ruth begins to practice law when she learns of Charles Moritz, a bachelor who takes care of his ailing mother but was denied the caregiver tax because he is not a woman and has never been divorced. Since the case is an example of a man who has been discriminated against because of his sex, Ruth believes challenging it could help the fight for gender equality.

Ruth seeks help from her old friend Mel Wulf, an employee at the American Civil Liberties Union, who first deems the case unwinnable but eventually agrees to help her represent Moritz. With Wulf’s help, the Ginsburg family begins to prepare their argument.

Between scenes of the Ginsburgs working on the case, the film’s final antagonists are introduced. Erwin Griswold, former Harvard University dean, and Ernest Brown, former Harvard University professor, conspire with young lawyer James Bozarth. All three think of ways in which they can maintain the country’s status quo and end all legal talk of gender equality.

Here, the film’s tone struggles. While the men who plan their argument against the Ginsburgs refuse to acknowledge the very apparent gender inequality, the portrayal of the lawyers is excessive. Instead of showing them as deeply flawed but realistic characters, the film paints them as villains who seem to have walked out of an entirely different film.

Hidden in dark rooms where cigar smoke curls lazily in the air and women are only allowed to sit prettily on the couches, the men speak in angry, authoritative tones as they build their case. Their desire to fight the Ginsburgs is no deeper than their need to maintain a strongly patriarchal society.

Although the film can be forgiven for lacking three dimensional villains since they do not appear until the final minutes, the men do not have to be stereotypically evil. Seeing Ruth fight against institutionalized sexism so ingrained in society that those who perpetrate it do not fully realize they are wrong would have been far more interesting than the moustache-twirling villains the film provides.

Despite this, the final scene, which takes place in the courtroom, is a wonderful resolution to Ruth’s hard work. While she fails to make an impact on the appellate court judges when she first speaks, Ruth’s rebuttal against Bozarth is wonderfully portrayed by Jones. Jones manages to convey Ruth’s fear, embarrassment and anger, and she shows how the famous justice channeled her emotions into a brilliant speech.

The Ginsburgs, Wulf and Moritz leave the courtroom triumphantly.

As text appears on the screen to inform the audience that the Ginsburgs won the Moritz case, the film cuts to Ruth climbing the steps of the Supreme Court building. She wears an outfit similar to the one she wore at the beginning of the film, but this time, Ruth walks alone.

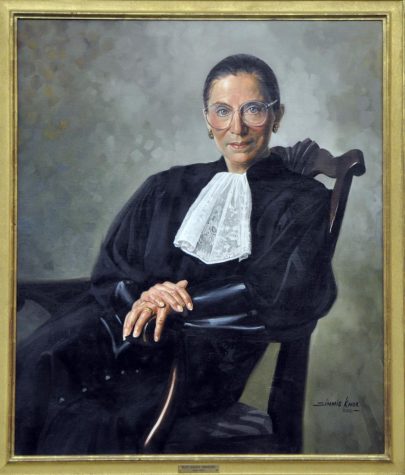

Recordings of the real-life Ruth arguing various cases play as she steps closer to the Supreme Court building. The camera’s view is momentarily obscured by a pillar, and when Ruth steps into the camera’s frame once more, it is the real Ruth rather than actress Jones who walks into the Supreme Court.

In a movie with stellar acting and a fascinating, well-paced plot, the final, slow shot builds to the reveal of the real-life Ruth Bader Ginsburg. Her appearance in the film reminds the audience that while parts of the plot adhere to the typical Hollywood formula, the core of the story is true: Ruth Bader Ginsburg is a revolutionary figure who was and continues to be a voice for the downtrodden.

Jones does a remarkable job of portraying the brilliant, self-conscious, determined Ruth, and her chemistry with Hammer’s Martin is easy and realistic. While the film suffers a bit beneath its villains, the message was powerful — even the most influential public figures had to begin somewhere, and Ruth started at the bottom.

“On the Basis of Sex” uses Jones’ talent to show that Ruth’s near-legendary status did not come easily, and the setbacks she encountered nearly broke her spirit. But with the single question from her daughter — Who was it all for, if not for me? — the audience is given a clear message.

This film, and Ruth’s work, always has been, and always will be, for all of us.

Lauren Trimber is a senior majoring in English and creative writing and minoring in political science. This is her third year on staff, and she will be...