Slow down and breathe: Workshop teaches art of meditation

Buddhist monk Thomas and nun Andersen lead campus mindfulness workshop

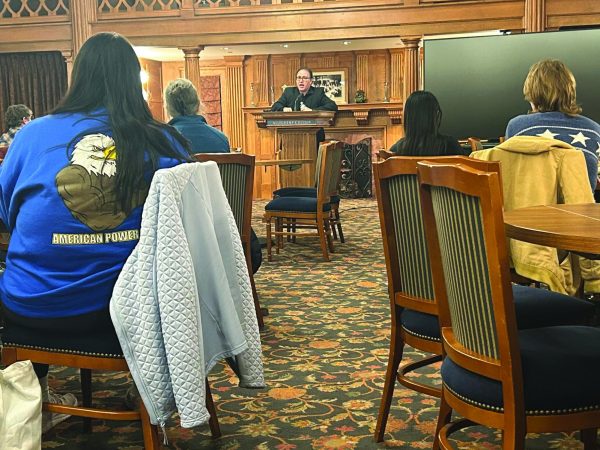

The second floor of Montgomery Hall was transformed from a dance space to a place of meditation for the Mindfulness Workshop on Saturday, Sept. 22.

Students and faculty members drifted into the room, sitting on black cushions around an ornate blanket, which was spread across the middle of the floor. Buddhist monk Claude AnShin Thomas, who is in residence at Allegheny College, stood near the altar on one end of the rug. Buddhist nun Wiebke KenShin Andersen sat near the altar with a bell both she and Thomas used to indicate certain parts of the ritual.

A Vietnam War veteran and Purple Heart recipient, Thomas said he sometimes uses a variety of meditation methods to connect himself with his breathing. In 2004, Thomas published a memoir titled “At Hell’s Gate: A Soldier’s Journey,” which describes his service in Vietnam and subsequent healing from the war.

While he grappled with post-traumatic stress disorder, Thomas’s life began to change when he attended a meditation retreat, according to the memoir’s online description. Since that encounter with Buddhist teachings, Thomas gradually became more involved in the practices until he was ordained as a Zen monk.

The workshop began with Thomas asking various participants to list the most important things in their lives. After receiving answers that included family and health, Thomas asked Andersen to cover his mouth and nose so he would be forced to hold his breath as long as possible to demonstrate that breath was the most important thing in his life.

“We constantly have the privilege to be a part of the nature of mind, nothing but mind. The nature of mind is something that transcends the intellect,” Thomas said. “You can’t think yourself into that place. Spiritual practice is not about what we think. It’s to come to a place beyond all intellect. It’s to understand the thoughts that we have are not absolute facts … thoughts are just thoughts. Some of them may be correct, some of them not.”

Thomas explained a disciplined spiritual practice allows mindfulness to grow, and breathing awareness in daily life is a key to that development. The foundation to that awareness is sitting meditation, Thomas said.

“I live with the reality of mortal injury, post-traumatic stress,” Thomas said. “I interact with the world as a result of that in a particular way. Sometimes, the anxiety that manifests itself in my life is such that I find sitting difficult. So, I walk.”

After Thomas explained the correct posture and position for sitting meditation, participants sat in about 30 minutes of meditation, a silence broken only by the clock’s rhythmic ticking and the occasional creak of Montgomery’s floor.

When the demonstration of sitting meditation was over, Andersen talked about the merits of walking meditation.

“Usually when we are walking, we are either still hanging on to what just happened or our mind already goes to where we are going. So, it’s seldom that we are really with mind and body in one place,” Andersen said. “The walking meditation … is slower and you are coordinating breath and steps in order to foster that (idea) of being with mind and body in one place.”

Andersen’s desire to focus her breathing and mind through Buddhist practice manifested when she was still living in Germany, where she was born and met Thomas. Thomas asked her to join him in a prayer walk from New York to San Francisco, Andersen said. Although Andersen did not originally anticipate staying in the United States after the walk, she said she has been doing work in both Germany and the United States since.

“My initial interest (in Buddhism) was personal suffering,” Andersen said. “I was young and confused. I thought there must be something that could support me … and I’ve found that … I consider it a privilege to be at a college.”

Similar to Thomas’s decision to demonstrate his need for breath before the sitting meditation, Andersen placed heavy emphasis on her breathing while she demonstrated walking meditation. Participants were instructed to breathe in when stepping with their right foot and breathe out when stepping with their left. Andersen suggested that everyone see how long they could stay in contact with their breath and steps.

Following the walking meditation demonstration, Andersen explained the benefits of eating meditation.

“This is the interesting part: it’s always new,” Andersen said. “You’re new, the food is new, the day is new. So, with eating meditation, we really slow the process down.”

Everyone was given an apple slice and told to chew every bite 50 times, which would allow them to slow down and connect with all the elements that come together to make the apple, according to Andersen.

“At some point, our species reached out to this object and decided to put it in their mouth to see if it was something that could nourish them,” Andersen said. “Now, we take it for granted … In Buddhist practice, we often refer to the suchness of something. If I don’t use the name, what is it? Can I experience it without immediately putting the label apple on it?”

Before attendants were allowed to eat the apple, a student volunteer read aloud a verse from “The Five Contemplations, ” which are phrases taken directly from what the Buddha instructed monks and nuns to ensure they would remain mindful when eating, according to “Lexicon of Food.”

As attendants prepared to leave the workshop after eating meditation, Andersen explained the benefits of working meditation, which allows participants to connect with the elements that affect their daily lives.

“In working meditation, we slow down and see if we’re in contact with our breath,” Andersen said.

Allegheny’s mindfulness challenges initially began with an idea from Professor of English and LGBT Minor Coordinator Jennifer Hellwarth, Chaplain Jane Ellen Nickell said. After Hellwarth brought the idea to faculty members, Nickell and Professor of Political Science Sharon Wesoky volunteered to help coordinate the event, according to Nickell. After the Year of Mindfulness, the positive response from students motivated the Office of Spiritual and Religious Life to initiate mindfulness challenges every year, Nickell said.

This year’s 30-Day Mindfulness Challenge began Wednesday, Sept. 12 with a sit-in at the Henderson Campus Center lobby. Weekly opportunities to practice mindfulness have been held since, with Thomas and Andersen helping throughout.

“It’s been a wonderful opportunity to have (Thomas and Andersen) in residence,” Nickell said. “I don’t know how many students the (Mindfulness Challenge) has helped, but even if one student has developed the ability for mindfulness, it’s been worth it.”