Partisan gerrymandering: An ongoing battle in PA

In June 2017, the Pennsylvania League of Women Voters filed a lawsuit against the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania for partisan gerrymandering. This lawsuit launched a state-wide movement that questioned the constitutionality of Pennsylvania’s congressional map, which had been in effect since 2011.

In January 2018, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court ruled the congressional map unconstitutional, and new congressional lines were drawn.

Partisan gerrymandering is the manipulation of district maps to favor a political party. Congressional and state legislative district maps are redrawn every 10 years in the United States.

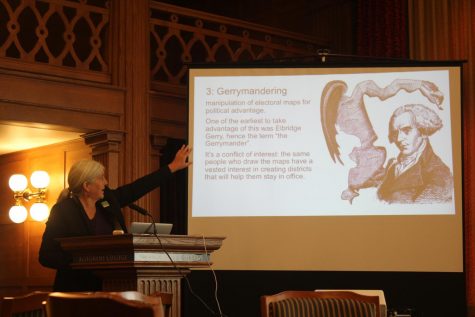

Chair of Fair Districts PA Carol Kuniholm spoke to students and community members about partisan gerrymandering in Pennsylvania at noon on Tuesday, Sept. 18, 2018, in the Patricia Bush Tippie Alumni Center.

“People think, ‘oh, now the problem’s over because we have new district lines,’ ” Kuniholm said prior to the event. “And it’s not over at all, because the process is still what it was. The process is still very secretive, very much controlled by leaders, and the state house and senate districts are still very badly gerrymandered.”

Allegheny’s Law and Policy Program and Center for Political Participation sponsored the Tuesday discussion, and Tom Cagle of Meadville, 68, helped organize the event.

“We were originally contacted by Kuniholm … (because) she’s doing a couple of events in the area in the upcoming week,” said CPP Fellow Alex Yarkowsky, ’21, prior to the event. “So when she said she had this time slot available on Tuesday, we did everything we could to make sure we could host her on campus.”

Since January 2016, Kuniholm has gone to 25 different districts throughout Pennsylvania to speak about partisan gerrymandering. Kuniholm said she became passionate about gerrymandering reform during her time as a pastor in Philadelphia, where she saw the inequity in public school systems that is linked to the state’s issue with gerrymandering.

Chair of Fair Districts PA Carol Kuniholm speaks about gerrymandering in the Patricia Bush Tippie Alumni Center Tuesday, Sept. 18, 2018.

Students and community members attend the presentation on partisan gerrymandering.

During the discussion, Kuniholm first outlined the process of partisan gerrymandering, and she explained that partisan gerrymandering begins with reapportionment. Some states grow in population over time, while others, like Pennsylvania, do not and may even decrease in population. Congressional seats in the House of Representatives must then be reallocated. This reallocation happens after every national census conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau.

“If a state is growing in population relative to other states, they get more seats,” Kuniholm said. “If they’re losing population relative to other states, they lose a seat … that triggers the next word, which is redistricting.”

Pennsylvania lost a seat in congress after the 2010 national census, and the state is predicted to lose another following the 2020 national census, according to Kuniholm. As the population changes, the congressional district lines are redrawn accordingly, but Kuniholm said state legislative lines must be redrawn as well, since the population shifts not only in the state but in different towns, cities and counties as well.

In Pennsylvania, a five-person commission comprised of state legislators redraws the state legislative lines after every national census, which has led to partisan gerrymandering in Pennsylvania, according to Kuniholm. The commission is not subordinate to anyone and can draw the district lines however they see fit.

Kuniholm said it is important to note that the United States is one of only two democracies in the world that allows its legislators to have any kind of involvement in the redistricting process. She said it is a conflict of interest, and all other democracies besides Malaysia have a separate body redraw their district lines.

State legislative districts in Pennsylvania are not drawn fairly, according to the Fair Districts PA website. Kuniholm explained different tactics politicians use to benefit themselves and their party, including Sweetheart gerrymandering, cracking and packing.

Kuniholm used Pennsylvania’s seventh district as an example of one that has been greatly affected by gerrymandering tactics over the last 60 years. It progressed from a “fairly reasonable district” to one that has been altered significantly and has been dubbed “Goofy Kicking Donald.”

“What changed?” Kuniholm asked.

She said one change that contributed to gerrymandered districts, like the seventh district, was advancements in mapping technology.

“Think about how much easier it is to do things with maps, even now (more so) than three years ago,” Kuniholm said. “In the past, gerrymandering was done with an actual paper map, pens and a thumbtack … now, mapping technology is amazing.”

Kuniholm said Pennsylvania is often regarded as the state most affected by gerrymandering in the United Sates. There are five different measurements to detect gerrymandering, which include “efficiency gaps,” “seats-to-votes,” “mean-median,” “simulated elections” and “lopsided wins.” Pennsylvania ranks as the most gerrymandered state by the efficiency gaps and seats-to-votes measurements, second by the mean-median, third by the simulated elections and fifth by the lopsided wins.

There is a solution to gerrymandering, but Kuniholm said lawsuits, like the one made by the League of Women Voters in 2017, are not the answer. Once the 2020 national census is conducted, Pennsylvania congressional districts will be redrawn once again and could deviate from the map redrawn in 2018.

Allowing state legislative district lines to be gerrymandered leads to a number of issues in Pennsylvania, including an impact on voters, according to Kuniholm.

“The impact on voters is, first of all, diminished engagement, but also lack of choice,” Kuniholm said. “If those districts are designed for one party or the other, nobody’s going to run against the party that it’s designed for. So, in 2016, 57 percent of our state legislative races had no opposition.”

For the 2018 midterm elections, 38 percent of seats in Pennsylvania’s House of Representatives are still unopposed, along with 24 percent of senate seats.

The situation is not much better for the many state legislators who strive to represent their districts, according to Kuniholm. “Good legislators” are often the targets of campaigns seeking to flip a district in favor of a certain party.

Bipartisan solutions are also fading away as legislators lose their sense of compromise for the betterment of all citizens, according to Kuniholm. She said there are “huge economic implications for the inability to come to bipartisan solutions.”

Since the founding of Fair Districts PA in January 2016, the organization has hoped for a constitutional amendment that changes the way districts are drawn. Kuniholm said state legislative districting requires an amendment because “the process is in our state constitution.”

The group has also been supporting bills to change the process of congressional districting and continues to encourage and build grassroot support for the cause — in addition to establishing more relationships with legislators.