Allegheny College hosts visiting English professor

Thompson speaks on race and casting choices in Shakespearian productions

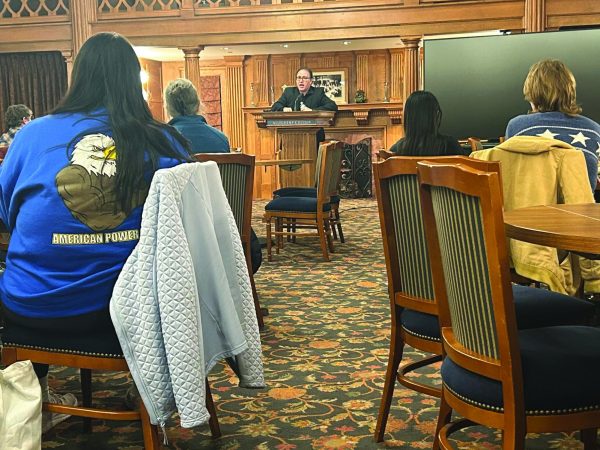

The Phi Beta Kappa Society of Allegheny College hosted this year’s visiting scholar, Ayanna Thompson, on Thursday, Feb. 16.

Ayanna Thompson is currently a professor of English at George Washington University. She specializes in the work of William Shakespeare and focuses her studies on issues of race.

Thompson’s lecture topics include “Shakespeare, Race, and Performance: What We Still Don’t Know,” “Encountering Othello Anew” and “Theorizing Revenge: or, Interdisciplinary Research as a Necessary Perversion.”

“It was really enlightening looking at Shakespeare from a different perspective,” Margaret Zella, ’20, said.

Over the last few months, Thompson has lectured at a number of elite colleges and universities including Rice University, University of the South: Sewanee, Mary Baldwin College and a handful of other prestigious institutions.

“This is my seventh out of nine campus visits this year. It’s been a real pleasure. I had the opportunity to teach a class this afternoon and I can attest that Allegheny students are quite special,” Thompson said.

Thompson began her lecture by quoting Comedian Paul Mooney. The quote compared race to an elephant in the room that is spraying diarrhea all over the audience, yet everyone refuses to mention it.

“Like the Black American Comedian Paul Mooney, I find it impossible to ignore the shitting elephant in the room. Notions, construction and performances of race continue to define the contemporary American experience, including our conceptions, performances, employments of Shakespeare, ” Thompson said.

Thompson explains her reactions to Shakespeare aren’t normal. Thompson, unlike most of her colleagues, is not a trained Shakespearean. “In many respects, I am an utter and complete fraud,” Thompson said. She views Shakespearean studies as a form of practical humanities.

“I will raise more questions than I answer,” Thompson said before beginning her lecture.

Thompson said she had divided her lecture into three distinctive parts. The first section of her lecture included a brief overview of the history of nontraditional Shakespeare casting.

“There’s a long and rich history of Shakespeare performed by actors of color for both political and artistic reasons,” Thompson said.

Thompson went on to explain that in the 19th Century, Shakespearean monologues and soliloquies allowed black actor, Ira Aldridge, to rise to international fame.

Aldridge was an American born actor who was commonly casted in scenes of Shakespeare’s Othello, but was not limited to Shakespeare’s black roles. Instead, Aldridge experimented with white face performances.

“Thus beginning the history of non-traditional Shakespeare,” Thompson said.

“It was nice hearing [Thompson] talk about how different choices in casting Shakespeare really do make a difference,” Bethany Schwartz, ’20, said.

The second section of the lecture provided an overview of perception studies for Shakespearean theatrical productions to demonstrate that the current methodologies are not adequate.

“Today, many theater companies practice non-traditional casting,” Thompson said.

Thompson explained that non-traditional casting refers to the selection of colored actors in roles that were initially imagined as White.

A commonly known method of non-traditional casting is “colorblind casting.” In this practice, the race of the actor is not supposed to impact the interpretation of a play or character.

Another type of non-traditional casting is “unconscious casting,” which refers to choosing actors whose race and characteristics are intended to bring meaning to the character.

The final type of non-traditional casting is “cross-culture casting,” which is where the entire play is set somewhere else.

“It is important to remember that each audience is made up of individuals who bring their own cultural reference points, political beliefs, sexual preferences, personal histories and immediate preoccupations to their interpretations of a performance,” Thompson said.

Thompson continued to point out the different issues with reception theories that are used to understand an audience’s response.

First, Thompson acknowledged the problems with the most commonly used methodology, the anecdote. The anecdote method focuses on the viewing experiences of one or two audience members and then assigns that perspective to the audience as a whole.

“I am far from the first scholar to note that the study of reception in theater studies has been a stunted field of inquiry to date,” Thompson said.

Thompson says that she finds herself relying too heavily on the unreliable methodology of the anecdote.

The third and final section concluded with an examination of contemporary race studies about how audiences make sense of the what they see on stage.

“Now I can imagine that one might argue that I’m asking others to look for something that is not there,” Thompson said. “I’m not asking if race impacts an audience’s reception. Instead, I assume that race impacts an audience’s reception and I’m asking how the impact manifests itself.”

“I don’t know that there is one person who can solve this alone,” Thompson said.

Thompson concluded her discussion by encouraging students of all different majors ranging from Computer Science to Theater to study how race influences the receptions of audiences.

“You guys can do this big thing that can actually change where we are. 200 years with no data. You can change that,” Thompson said.