A love story: Explicable systems, inexplicable feelings

Neuropsychology provides insight into this ‘Crazy Little Thing Called Love’

Mystery chocolates disgust or delight, roses dance across the country and drug store shelves are ravaged for cards containing strangers’ poetry. Together, these breed a frenzied phenomenon — Valentine’s Day.

American consumers were expected to spend a total of $19.6 billion on Wednesday, according to the National Retail Federation’s annual Valentine’s Day survey.

Quantifying Valentine’s Day in any way may be adversarial to feelings of love and romance, but exploring the neurological science of love may contribute to a greater understanding of human relationships and of $19.6 billion in consumer spending.

The current leader in love research is Helen Fisher, biological anthropologist, senior research fellow at the Kinsey Institute of Indiana University in Bloomington, Indiana, and chief scientific adviser for Match.com.

A 2006 study titled “Romantic Love: A Mammalian Brain System for Mate Choice” — led by Fisher and published in the U.K. journal, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B — used MRI technology to analyze the brains and behaviors of people in love relative to the brains and behaviors of people not in love.

A person in love may feel energized, emotionally dependent and will often have an active sympathetic nervous system, commonly identified as the “fight or flight” response, according to the 2006 study.

“Smitten humans also exhibit empathy for the beloved; many are willing to sacrifice, even die for this ‘special’ other,” the study reports.

Based on the MRI results and these behaviors, as well as evidence from other studies, Fisher and her colleagues determined the specific brain structures and neurological pathways activated by love.

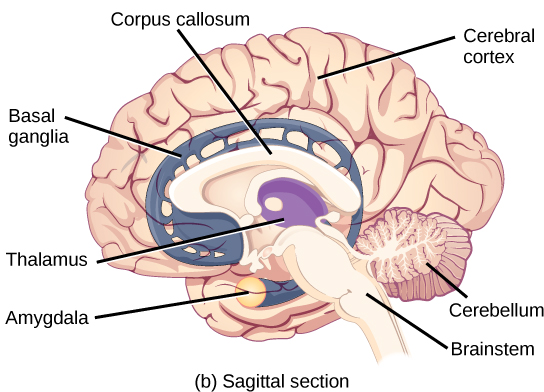

Three categories of love are associated with three different, yet connected, brain structures in the limbic system, according to the study.

Reactions and feelings of love begin in limbic system structures, especially in the basal ganglia.

Fisher separates activity in the amygdala for sex drive, activity in the caudate nucleus and nucleus accumbens for attraction and activity in the ventral pallidum for attachment and explains the role of each category in mate choice for mammals.

“The sex drive evolved to motivate individuals to seek a range of mating partners; attraction evolved to motivate individuals to prefer and pursue specific partners; and attachment evolved to motivate individuals to remain together long enough to complete species-specific parenting duties,” the study reports.

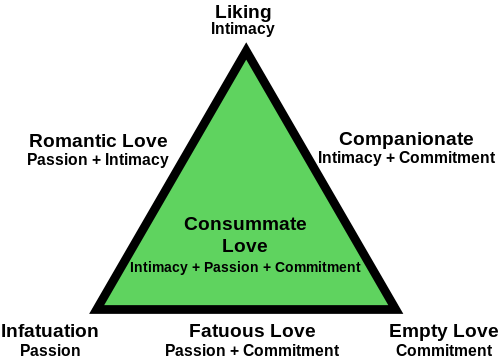

These categories overlap with American psychologist Robert Sternberg’s theory of love, which combines intimacy, passion and commitment to generate seven types of love, according to Juvia Heuchert, professor of psychology and clinical psychologist.

Robert Sternberg’s theory of love involves three basic components: intimacy, passion and commitment. Combinations of these components generate distinct types of love.

The compounds most responsible for components of love are dopamine, norepinephrine and serotonin, according to Fisher.

In Fisher’s 2004 book, “Why We Love: The Nature and Chemistry of Romantic Love,” Fisher hypothesizes elevated levels of dopamine are responsible for symptoms of craving for and dependency on one’s love.

In fact, these elevated levels of dopamine are nearly identical to the brain activity that occurs when one is addicted to drugs, according to Sarah Conklin, associate professor of psychology and neuroscience chair. While drug abuse and romantic love are both tied closely to dopamine activity in the brain, society’s reaction to the two are radically different, Conklin said.

“You know that while that’s a wonderful thing that you’re experiencing, it’s interesting that the same neurological pathway that governs these two really different kinds of behaviors are so differential accepted by society,” Conklin said. “We judge people who are addicted to meth, but we think it’s wonderful when you’re addicted to another person.”

In addition to dopamine’s addictive properties, Fisher hypothesizes that norepinephrine’s stimulation of energy as well as the obsessiveness associated with low levels of serotonin are also important in feelings of romantic love.

The limbic system and these compounds, however, cannot provide the fullest profile of love and are not exhaustive characterizations, Fisher argues.

“Regardless of what one knows about this subject, we all feel the magic,” Fisher writes in her 2004 book. “Romantic love is deeply threaded into our human spirit. If humanity survives on this planet another million million years, this primordial mating force will still prevail.”

Other biological pathways and psychological principles help characterize love, and one need only read a book, watch a film or listen to a song to discover the historical and cultural pervasiveness of romantic love.

“So the poets and the songwriters have succeeded in describing aspects of love, but for each individual that love is so unique and so complex that they have to write their own poetry in order to describe what it feels like,” Heuchert said. “And some of that poetry comes, I think, through the lovely experience of emotional intimacy with another person.”

Fisher posits love is emotional and can elicit heroic, even sacrificial behavior. A person may die on behalf of their beloved, and great storytellers have also brought love in conversation with death.

Romeo and Juliet, Pyramus and Thisbe and Cleopatra and Mark Antony famously died so they would not have to live without their respective lovers.

Love is present in such stories, in real celebrations of 50-year wedding anniversaries, in any way a person feels most loved, in two pairs of eyes meeting — perhaps for the first or thousandth time — and especially in contemporary music.

Song, as a means of communication, is intimate and inspires feelings of love. Love songs make internal chemical processes visible. A smile, a tear, many tears, a sigh or a laugh are manifestations of the love built in the brain.

When artists sing about sex, their words reflect Fisher’s sex drive component of love. “You Really Got Me” by the Kinks and Marvin Gaye’s “Let’s Get it On” are two examples among countless others.

Songs about love and craziness indicate the addictive properties of dopamine-dependent love as well as the attraction component Fisher describes in her work.

Beyonce’s song, “Crazy in Love,” from her album “Dangerously in Love,” Queen’s song, “Crazy Little Thing Called Love” and Willie Nelson’s song, “Crazy,” made famous by Patsy Kline, all have lyrics reflective of addictive attraction.

Other artists sing about love’s timelessness.

Whitney Houston’s iconic performance of “I Will Always Love You” in the 1992 film “The Bodyguard” gives power to long-term feelings of love. Similarly, “Come What May” from the 2001 film “Moulin Rouge!” repeats, “I will love you, until the end of time.”

Written by Willie Nelson and originally performed by Dolly Parton, “I Will Always Love You” became one of Whitney Houston’s most famous ballads.

Queen’s Freddie Mercury wrote “Crazy Little Thing Called Love” in 1979, which helped launch the band’s “Crazy Tour” in the United Kingdom.

The love in each of these songs is so different, indicative of Heuchert’s belief that love is different for each character, artist and person.

While love may vary greatly from person to person, it should not discourage us from attempting to come to a greater understanding, according to Conklin.

“Just because something’s difficult to measure, doesn’t mean it shouldn’t be measured,” Conklin said. “It just means it has to be measured carefully. Measurement of human behavior is messy and complicated. It is a big beautiful mess.”

Heuchert echoed Conklin’s reflections.

“Love is a beautiful — and the most enjoyable — mystery,” Heuchert said.