A glimpse into Prince’s ‘Key Metaphors in Daughter’s Exchange’

Final faculty lecture series focuses on the importance of language

Professor of English and Black Studies Valerie Prince traveled to West Africa during the summer of 2016. This photograph is one that Prince shared during her lecture. It shows a marketplace, a space in which women called to one another and Oriki practice could be observed.

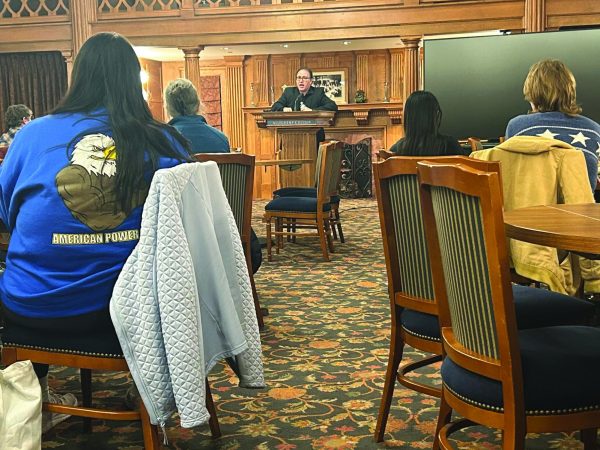

The final installment of the 2016-2017 Karl W. Weiss Faculty Lecture Series featured Associate Professor of English and Black Studies Valerie Sweeney Prince on Wednesday, April 12.

The faculty lecture series has featured monthly presentations by Allegheny faculty from the history, psychology, modern and classical languages, English and political science departments throughout the 2016-2017 academic year.

“The idea is simply to create a place for faculty from different disciplines to share their work,” said Patricia Rutledge, professor of psychology and chair of the Academic Support Committee.

Prince presented “Key Metaphors in Daughter’s Exchange,” a discussion of themes and ideas in her forthcoming book, “Daughter’s Exchange: The African American Woman’s Encounter with the Intellectual Marketplace.”

Prince’s initial research for “Daughter’s Exchange” began in 2000 and has since evolved into the manuscript she presented.

Prince framed her presentation around the marketplace of intellectual exchange, one of the two key metaphors her work discusses.

“Traditional academic discourse favors the semblance of objective universal truth by masking the agent behind the language,” Prince said. “I want to resist this move by drawing on Oriki as an African and woman-centered oral practice.”

Oriki is a Yoruba practice that is often characterized by the calling and chanting of names and community relationships to engage and support one another, according to Prince.

A grant from the Academic Support Committee provided Prince the opportunity to travel to West Africa in the summer of 2016. She shared a photograph she took on her trip of a literal marketplace, a space in which women called to one another and Oriki practice could be observed.

The presentation then followed the paths of three major ideas — the body, the mind and the integration of the two to operate within an Oriki-inspired model of the academic world.

Addressing the body, Prince discussed Saartjie Baartman, a black woman exploited and exhibited in “freak shows” in the early 1800s.

“She spoke several languages,” Prince said. “They didn’t see her mind; they saw instead her body. They overlooked her intelligence, her ambition and her courage, and Europeans paid to see her black butt.”

After Baartman died, her body became an opportunity for French scientists to exploit her further, reduce her to meat and study her as an inhuman artifact, Prince said.

While this historical description of Baartman addressed the body, Prince shared ideas from Plato’s “Symposium” about education to address the mind.

Prince described the Symposium model by comparing it to a full glass of water emptying into an empty glass. This image, she said, represents the dynamic between the labels of “teacher” and “student.”

In this model, the teacher essentially impregnates the empty student with knowledge that only comes from the teacher, Prince said. She continued to argue that this metaphorical pregnancy exists only at the level of the mind, not the body, and does not integrate the experience or expression of the teacher or student.

“[The Symposium model] simply does not work for me,” Prince said.

Intellectual exchange should encompass the body’s ability to express, the mind’s ability to think and especially the historically-erased experiences within each of those realms, according to Prince.

At the core of her work is the development of a new fundamental model of existing in the intellectual marketplace, Prince said.

Through her research journey, Prince said she has discovered that this new model can be based on elements of Oriki and the ways in which personal experiences and histories have the power to inform knowledge.

She shared images of a collage, Toni Morrison’s “Black Book” and a busy crosswalk to demonstrate the limitations of language and the power of using experiences to think and create.

Prince then shared an image of a school of fish and a flock of birds in flight, consisting of young and old individuals, to represent the shared knowledge among them — that each knows what to do within the school or flock.

“So, what does this school have in common with this school?” Prince asked as she likened the image of the fish to an image of Allegheny.

Language often allows people to avoid truly learning — especially with respect to sustained dialogues on campus — but we can learn from Oriki and what it can do to enhance language, being and behavior among students and faculty, according to Associate Director of the Inclusion, Diversity, Equity, Access and Social Justice Center Darnell Epps.

“I think we need to be more understanding and think more critically about language and its purpose,” Epps said. “I especially love how [Prince] was validating and building on the experiences of students.”

Prince mentioned her Feb. 9 presentation and student performance of her work “Waterbearer” as an example of expressing knowledge and experience in a way that is whole, encompassing the body, the mind and experience in an exchange of academic art with the audience.

Her final reflection of the Symposium model of education and the model she strives to use — the Oriki model — revealed the two cannot be compared to one another. They are not the same, and they do not accomplish the same things, she said.

“I don’t want to ever do this,” Prince said as she pointed to the image of the water pouring from one glass to another — the Symposium model. “It can work. It’s a way that teaching and learning does happen. It’s a way that writing has happened, and it often gets rewarded.”

She then pointed to the image at the birds in flight.

“But this is what I’m driving at in Daughter’s Exchange,” Prince said.