Allegheny Listens program addresses Islamophobia

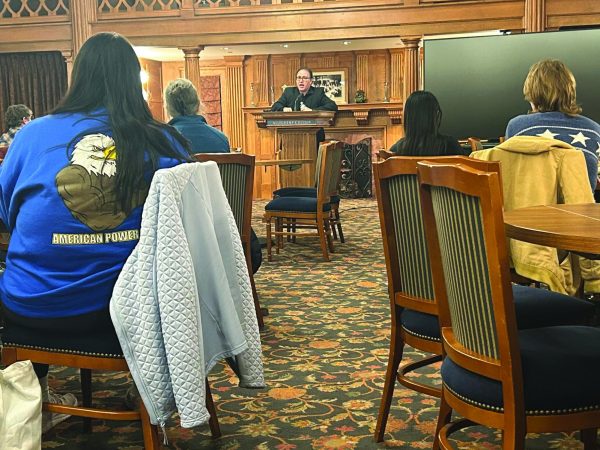

Edward Curtis IV, professor of religious studies at Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, delivers a speech on Islamophobia in the U.S. on Thursday, Sept. 22, 2016. The speech was part of the inaugural Allegheny Listens event, an extension of first-year orientation.

The Allegheny and greater Meadville community gathered in Shafer Auditorium on Thursday, Sept. 22, for the inaugural Allegheny Listens: A Dialogue on Islamophobia.

The dialogue consisted of two main components: a moderated discussion panel with two guest speakers, and a following breakout session for all first-year seminar classes that was led by a volunteer faculty or staff facilitator.

President James Mullen opened the dialogue, emphasizing the importance of the moment and thanking everyone for their commitment to Allegheny’s statement of community.

“It’s not just another meeting—it is a very important moment about what we represent in this time and in this place at Allegheny College,” said Mullen. “The challenge for all of us is, today going forward, to stand for the world as a place that cares and respects and celebrates … and builds community together.”

Mullen was then followed by Nadiya Wahl, ’17, a student ambassador for the Year of Mindfulness, who explained to the crowd that the main goal of the Year of Mindfulness is to pause and reflect on one’s everyday life. She asked the crowd to center in on the present moment and how each of the members of the crowd were related and to speak with intention, thoughtfulness and respect.

“Remember that your words and actions do matter,” said Wahl.

Edward Curtis IV, professor of religious studies at Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, spoke first and gave an overview of the historical roots of Islamophobia.

The government has essentially institutionalized and legalized Islamophobia,[/pullquote]“Islamophobia—that is, the irrational fear of Muslims—is deeply rooted in our historical DNA as Americans,” said Curtis. “It has been with us since we have existed as a distinct political entity. Because it is so deeply rooted, it is going to be very, very hard to change. It will take work. Otherwise it will get worse. It certainly has gotten worse since … 2000,” Curtis said.

Curtis gave a historical overview of the causes and development of Islamophobia and how it has become so deeply embedded in American culture. He traced these roots back to early trading between America and North African countries in the 17th century, explaining that more than 100 years of saying that Muslims are not good people developed into Muslim becoming an epithet.

Curtis linked this use of “Muslim” as a derogatory and offensive term to rhetoric used against Obama in 2008 and still in 2016.

“These themes are not new,” said Curtis. “They are old and that is why they are awfully hard to get rid of. They are the storehouse of American culture.”

In tracing the history of Islamophobia, Curtis also discussed the rise of Islamophilia—an irrational love of Muslims—that arose in the 1800s.

Curtis said Islamophilia portrayed Muslims as sensuous and erotic people, and the orient was seen as playful and fun. This was used ultimately as a way to market materials, like Camel cigarettes. Islamophilia also introduced ideas of sexual violence and the corruption of the “pure white women” by charming, Arabian men.

Following World War II, a new period of Islamophobia developed where the government actively spread information about the Nation of Islam which it saw to be a threat to national and foreign interests.

“In the 1960s, the face of Islamophobia was no longer brown; it was black,” said Curtis.

This led to Islam becoming more associated with Islamophobic ideas than Islamophiliac ones, according to Curtis.

“There is seldom a religious prejudice that is not somehow stoked and encouraged by political conflicts. And you and I and all of us together can solve political conflicts,” said Curtis. “All of our Islamophobia may take the form of—and may be an expression of—what sounds to be religious, but its root is often political.”

Curtis emphasized throughout his talk the portrayal of Muslims as everything that Americans are not.

He explained how attributing the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks to the entire Muslim population, rather than solely blaming al-Qaida, targeted Muslims as enemies of America.

Prior to his speech, Curtis said he hopes to reach people who are unfamiliar with anti-Muslim prejudice and ultimately motivate them to help himself and everyone else trying to challenge this prejudice.

“Islamophobia is a critical issue to American life, and we all need to be talking about it,” said Curtis. “If we can challenge it, we can make our country a better place for everybody. It helps if we all challenge anti-Muslim views in our daily life. That’s something we can all do. But we also need to challenge the government and the media.”

Maha Hilal, executive director of the National Coalition to Protect Civil Freedoms, followed Curtis, and spoke about the institutional nature of Islamophobia in America and how society is simply mirroring the Islamophobia that is embedded in U.S. national politics.

She began with examples of policies that directly target Muslims, such as the The National Security Entry-Exit Registration System, which requires individuals from 23 countries, a majority of them Muslim, to register with the government.

“Initially, many of the public policies … targeted non-citizens,” said Hilal. “Subsequently, and years later, the policies increasingly began to target citizens.”

Hilal then discussed the use of torture in the war on terror, not only at Guantanamo Bay, but in domestic prisons as well.

“The government has essentially institutionalized and legalized Islamophobia,” said Hilal.

She listed 12 of the the worst findings from the CIA torture report. These included rectal feeding as a way to control prisoners, as well as a prisoner who froze to death while being chained to the floor, one who had his eye removed and how detainees who were put in diapers and withheld access to proper bathroom facilities.

Hilal also discussed the rise in hate crimes since Sept. 11, stating that prior to the attacks, the number of yearly incidents of hate crimes was around 20-30. In 2001, that number rose to 481 incidents, and has not dropped below 100 incidents since. According to Hilal, hate crimes are at an all time high since Sept. 11.

“[Islamophobia] is not only affecting Muslims at an institutional level, [but] it is also affecting Muslims at a societal level. [These are] not discrete acts, they are interconnected. What the state does is connected to how society is responding,” said Hilal. “When the state, or the U.S. government sets the precedent for a particular type of treatment of a group, whether it is Muslims … or blacks … the state is sending a message to society that this type of treatment of this group is acceptable.”

She explained how the precedent set by the government implies to members of society that they will not be held accountable for committing hate crimes.

“[It is] important to think about how this is impacting Muslims in your communities on the ground,” said Hilal. “This is not just about rhetoric, this is about the practical and concrete consequences of when muslims are being targeted on many different levels.

“It is not enough to simply work within your communities and societies,” said Hilal. “It requires us to look at and challenge the systems of oppression that help keep Islamophobia in place.

“It’s not going to be solved by the muslim community. It’s going to be solved when everyone in this society … works together to dismantle these systems of oppression.”

The dialogue then opened up to questions from the crowd before the first-years broke up and gathered into their first-year seminar classes and discussed the dialogue further.

Darnell Epps, associate director of the Inclusion, Diversity, Equity, Access and Social Justice Center, was a volunteer group facilitator for the break out session.

“The goal [is] to get students to talk and to learn how to dialogue about these issues,” said Epps. “Often times we are taught how to debate. How … we have a two-way dialogue about things that we don’t always agree with—that’s the goal of the facilitators, to help students engaged in those conversations.”

Epps believes that dialogue can be a useful teaching method.

“When we dialogue, we can clarify misunderstandings,” said Epps. “We can challenge our own bias, and sometimes we are able to challenge things that we didn’t really consciously know we had, especially if the education isn’t there. If the only thing you know about a certain religion is what is portrayed in the media, or how some people have radicalized it, I feel like you would really miss out on what it is, or the good aspects.”

The dialogue was funded through the Mellon Internationalization Grant, a $675,000 grant that was awarded to the college in 2012 and helped bring the two guest speakers to campus.

“It’s been a joint effort, very large in scale, bringing together both the Mellon Internationalization Grant, the Dean of Students Office, Ande Diaz’s office, the Middle East and North Africa faculty and also the Year of Mindfulness,” said Laura Reeck, associate professor of modern and classical languages and co-principal investigator on the Mellon Internationalization grant.

The dialogue is part of a pilot program for first-year students.

“The idea is that it would be repeatable as that ‘Allegheny Listens’ every year in the context of orientation, whether it would grow to larger programing, I’m not sure. Every year it would be ‘Allegheny Listens,’ but the topic would be different,” said Reeck.

The topic of Islamophobia tied into both the Internationalization grant as well as current events.

“We can be very quick as a society, and especially in the media, to target an entire religion for the acts of a hateful few. For us to judge an entire group based on those acts—I don’t think that’s right,” said Epps. “We have members of our community … who are muslim. I feel like we have a responsibility here on this campus, to seek to understand, to treat people civilly. And again, that’s not to say we always have to agree, but there is a way that we have to engage in dialogue and be respectful. And that’s what I’m hoping we’re going to talk about with the statement of the community and how we reconcile some of those tensions.”

Correction: In an earlier version of this story, The Campus stated that the IDEAS Center was the Inclusivity, Diversity, Equity, Access and Social Justice Center. It is the Inclusion, Diversity, Equity, Access and Social Justice Center. Updated Thursday, Nov. 14, 2016, at 9:29 p.m.